This week, the US Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rate for 0.5% to 0.75% for just the second time since the financial crisis of 2008, arguing that the American economy was expanding “at a healthy pace”. The Fed’s monetary committee also indicated that it planned to hike its policy rate at least three times in 2017 on the grounds that economic growth, employment and inflation were picking up and President-elect Trump’s proposed policies of cutting corporate taxes and boosting infrastructure spending could accelerate US economic recovery. “My colleagues and I are recognizing the considerable progress the economy has made,” said Janet Yellen, the Fed’s chairwoman, “We expect the economy will continue to perform well.”

There is a certain irony in Yellen’s statement given that this time last year, in hiking the policy rate for the first time in nine years, she made a similar declaration of confidence in the economy and then economic growth slowed to a trickle and the Fed postponed any further hikes.

The US economy has expanded on average by only 2% a year since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. The unemployment rate has dropped to more or less the same level as before global financial crash, but investment and productivity growth has been very weak.

Back last December, I raised the question that, given weak business investment hiking interest rates might push a layer of US companies into difficulty and trigger a new recession or slump. Indeed, that was why the Fed held off further hikes during this year.

So are things that much better that this risk of rising interest rates triggering a recession is now over? Well, Yellen described the rate increase as “a vote of confidence in the economy.” And the justification for this comes from somewhat improved figures of real GDP growth in the third quarter of this year, at a 3.2% annual rate. However, the pick-up was all in housing and inventories (building up stocks not sold), while business investment stayed flat. And on a year-on-year basis, US real GDP was higher by only 1.6%, while business investment contracted by 1.4%.

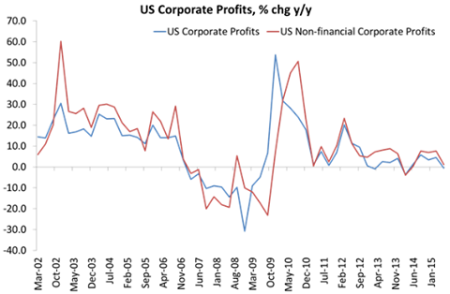

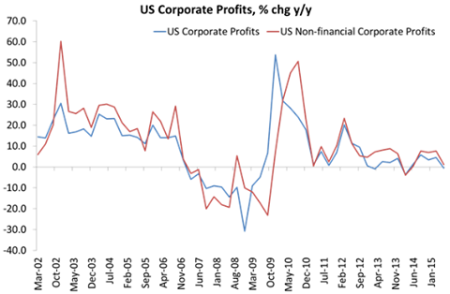

However, after falling in Q2, corporate profits rose in Q3, up 6.6% compared to Q2 and higher by 2.8% from Q3 2015. So it could be argued that the US economy is doing better in the second half of 2016 than in the first half, which was dire. House prices have surpassed their pre-recession peak and consumer confidence is at a new high.

Globally, corporate profits also picked up in the third quarter of 2016. A weighted average of five key economies, US, China, Japan, Germany and the UK) saw profits rise by over 5% yoy. Along with rising business activity indicators in the US and Europe, it seems that the major economies have staged a bit of a recovery in third quarter. But global business investment growth remains weak.

There are two risks that could undermine Yellen’s confident forecast (for the second time. The first is that rising interest rates will lead to increased costs of servicing corporate and household debt that cannot be funded through extra profits or real incomes in households. So default rates on debt obligations will rise.

There has been no real reduction in the build-up of private-sector debt in the major economies that took place in the early 2000s and culminated in the global credit crunch of 2007. That accumulated debt took place against a backdrop of favourable borrowing conditions—low interest rates and easy credit. Between 2000 and 2007, the ratio of global private-sector debt to GDP surged from about 140% to 163%, according to the IMF.

Public sector debt mushroomed after the global financial crash to bail out the banks and fund spending on unemployment and other benefits. The average level of public debt to GDP rose from 34% pts to roughly 90% – a post-1945 record. Combined with private-sector debt, the level of total nonfinancial borrowing to GDP in the advanced capitalist economies is actually higher today than it was in 2007.

In the emerging economies, after the Great Recession the increase in private sector debt has been massive. China is in a league of its own, with a 96%-pt increase in its ratio to 205% of GDP. Even excluding China, the figures are still big, up 25% pts and at 92% of GDP for emerging economies. Indeed, the increase in the private debt to GDP ratio in the emerging economies outside China now exceeds what took place in the DM in the 2000s expansion.

Most of this extra debt is the result of corporations in these countries borrowing more to increase investment, but often in unproductive areas like property and finance. And much of this extra borrowing was done in dollars. So the Fed’s move to raise the cost of borrowing dollars will feed through these corporate debts.

Moody’s, the US credit monitoring agency, reckons that there is now $7trn of global government debt that will face downgrades for risk of default because of rising costs of financing if the US dollar stays strong and global interest rates start rising during 2017. That’s 16% of total global public debt. In 2016 anyway, there were 35 credit downgrades for country debt.

Nevertheless, stock markets in the major economies head towards new highs on the expectation that the major economies are on the road to sustained recovery and that Trump’s policies will stimulate spending and boost corporate profits next year.

I have already put huge question marks against the likelihood that Trump can achieve fast and sustained economic growth in the US with his policies. And I am not the only doubter. I have already referred to the views of Deutsche Bank and JP Morgan on likely economic recovery in the US in 2017.

Now huge private equity fund, Bridgwater Associates, is also doubtful about the expected economic recovery. Its founder, Ray Dalio, reckons that “This is not a normal business cycle; monetary policy will be a lot less effective in the future; investment returns will be very low.” Echoing the view presented, ad nauseam, on this blog, Dalio identifies a “short-term debt cycle, or business cycle, running every five to ten years but also a “long-term debt cycle, over 50 to 75 years.” He comments “Most people don’t adequately understand the long-term debt cycle because it comes along so infrequently. But this is the most important force behind what is happening now.” Dalio reckons that debt growth has outstripped the income growth in the form of profits and interest necessary to service the current levels of debt. Easy money and low central bank rates cannot counteract the rising costs of debt servicing for long.

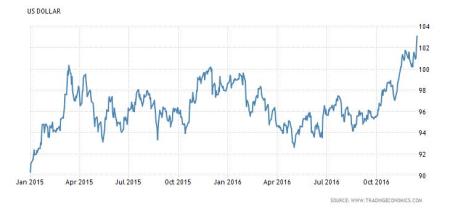

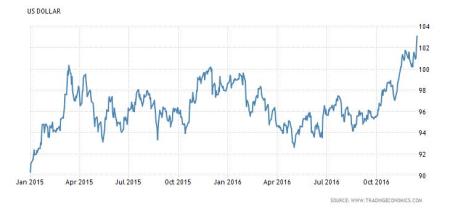

Now in 2017, it seems that the floor of interest rates globally, set by the Fed’s policy rate, is set to rise, if the Fed sticks to its plan to hike three more times and again in 2018. At the same time, oil prices are set to rise, assuming the OPEC oil producers stick to their plan to cut production. That will increase fuel prices and cut into corporate profits. And if the dollar stays strong against other major currencies, the servicing of dollar debt globally will jump, putting many corporations into difficulty.

So the relative recovery in global corporate profits and economic activity in the last part of 2016 may not last in 2017.

There is a certain irony in Yellen’s statement given that this time last year, in hiking the policy rate for the first time in nine years, she made a similar declaration of confidence in the economy and then economic growth slowed to a trickle and the Fed postponed any further hikes.

The US economy has expanded on average by only 2% a year since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. The unemployment rate has dropped to more or less the same level as before global financial crash, but investment and productivity growth has been very weak.

Back last December, I raised the question that, given weak business investment hiking interest rates might push a layer of US companies into difficulty and trigger a new recession or slump. Indeed, that was why the Fed held off further hikes during this year.

So are things that much better that this risk of rising interest rates triggering a recession is now over? Well, Yellen described the rate increase as “a vote of confidence in the economy.” And the justification for this comes from somewhat improved figures of real GDP growth in the third quarter of this year, at a 3.2% annual rate. However, the pick-up was all in housing and inventories (building up stocks not sold), while business investment stayed flat. And on a year-on-year basis, US real GDP was higher by only 1.6%, while business investment contracted by 1.4%.

However, after falling in Q2, corporate profits rose in Q3, up 6.6% compared to Q2 and higher by 2.8% from Q3 2015. So it could be argued that the US economy is doing better in the second half of 2016 than in the first half, which was dire. House prices have surpassed their pre-recession peak and consumer confidence is at a new high.

Globally, corporate profits also picked up in the third quarter of 2016. A weighted average of five key economies, US, China, Japan, Germany and the UK) saw profits rise by over 5% yoy. Along with rising business activity indicators in the US and Europe, it seems that the major economies have staged a bit of a recovery in third quarter. But global business investment growth remains weak.

There are two risks that could undermine Yellen’s confident forecast (for the second time. The first is that rising interest rates will lead to increased costs of servicing corporate and household debt that cannot be funded through extra profits or real incomes in households. So default rates on debt obligations will rise.

There has been no real reduction in the build-up of private-sector debt in the major economies that took place in the early 2000s and culminated in the global credit crunch of 2007. That accumulated debt took place against a backdrop of favourable borrowing conditions—low interest rates and easy credit. Between 2000 and 2007, the ratio of global private-sector debt to GDP surged from about 140% to 163%, according to the IMF.

Public sector debt mushroomed after the global financial crash to bail out the banks and fund spending on unemployment and other benefits. The average level of public debt to GDP rose from 34% pts to roughly 90% – a post-1945 record. Combined with private-sector debt, the level of total nonfinancial borrowing to GDP in the advanced capitalist economies is actually higher today than it was in 2007.

In the emerging economies, after the Great Recession the increase in private sector debt has been massive. China is in a league of its own, with a 96%-pt increase in its ratio to 205% of GDP. Even excluding China, the figures are still big, up 25% pts and at 92% of GDP for emerging economies. Indeed, the increase in the private debt to GDP ratio in the emerging economies outside China now exceeds what took place in the DM in the 2000s expansion.

Most of this extra debt is the result of corporations in these countries borrowing more to increase investment, but often in unproductive areas like property and finance. And much of this extra borrowing was done in dollars. So the Fed’s move to raise the cost of borrowing dollars will feed through these corporate debts.

Moody’s, the US credit monitoring agency, reckons that there is now $7trn of global government debt that will face downgrades for risk of default because of rising costs of financing if the US dollar stays strong and global interest rates start rising during 2017. That’s 16% of total global public debt. In 2016 anyway, there were 35 credit downgrades for country debt.

Nevertheless, stock markets in the major economies head towards new highs on the expectation that the major economies are on the road to sustained recovery and that Trump’s policies will stimulate spending and boost corporate profits next year.

I have already put huge question marks against the likelihood that Trump can achieve fast and sustained economic growth in the US with his policies. And I am not the only doubter. I have already referred to the views of Deutsche Bank and JP Morgan on likely economic recovery in the US in 2017.

Now huge private equity fund, Bridgwater Associates, is also doubtful about the expected economic recovery. Its founder, Ray Dalio, reckons that “This is not a normal business cycle; monetary policy will be a lot less effective in the future; investment returns will be very low.” Echoing the view presented, ad nauseam, on this blog, Dalio identifies a “short-term debt cycle, or business cycle, running every five to ten years but also a “long-term debt cycle, over 50 to 75 years.” He comments “Most people don’t adequately understand the long-term debt cycle because it comes along so infrequently. But this is the most important force behind what is happening now.” Dalio reckons that debt growth has outstripped the income growth in the form of profits and interest necessary to service the current levels of debt. Easy money and low central bank rates cannot counteract the rising costs of debt servicing for long.

Now in 2017, it seems that the floor of interest rates globally, set by the Fed’s policy rate, is set to rise, if the Fed sticks to its plan to hike three more times and again in 2018. At the same time, oil prices are set to rise, assuming the OPEC oil producers stick to their plan to cut production. That will increase fuel prices and cut into corporate profits. And if the dollar stays strong against other major currencies, the servicing of dollar debt globally will jump, putting many corporations into difficulty.

So the relative recovery in global corporate profits and economic activity in the last part of 2016 may not last in 2017.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario