Optimism for global economic growth remains. But the acceleration in 2017 from the low growth rates experienced in 2015-6 now seems to have paused in the first quarter of 2018. To greet the semi-annual meeting of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington to discuss latest economic developments, Maurice Obstfeld, the IMF’s chief economist, stated that “the world economy continues to show broad-based momentum.” But “against that positive backdrop, the prospect of a similarly broad-based conflict over trade presents a jarring picture.”

The IMF hiked its forecast for global real GDP growth to 3.9% for this year and in 2019. This improvement from the poor levels of 2015 and 2016 is based on rising investment and a recovery in world trade (which now seems to be threatened). The major economies of world capitalism are doing better but the idiocies of protectionism in trade by the likes of Donald Trump are threatening that recovery. That seems to be the main worry.

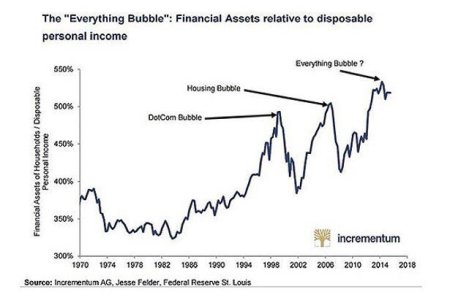

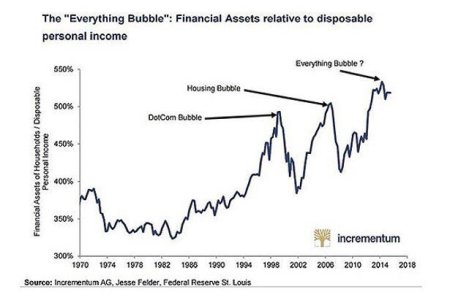

But Obstfeld is worried about the high levels of global debt, in households, corporations and governments. With interest rates set to rise, as the US Fed and possibly other major central banks start to raise their policy rates, the cost of servicing record-high debt will rise. That threatens further investment in productive (value-creating) assets and also instability in financial markets.

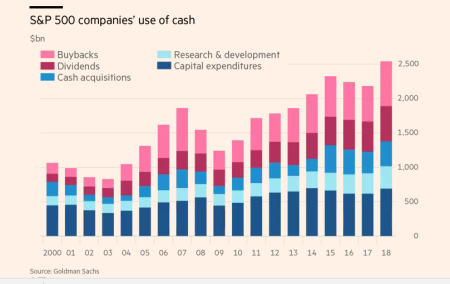

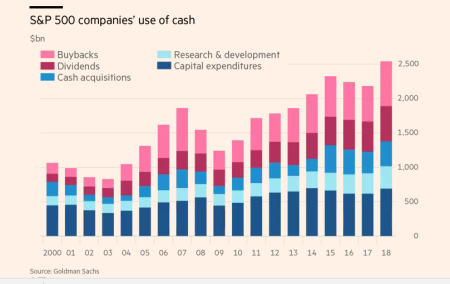

There has already been a ‘correction’ in world stock markets of about 13% since the beginning of the year as financial speculators begin to worry about an international trade war and rising costs of debt. And that is despite the huge handouts in tax cuts for US corporations introduced by Trump. Those tax cuts have sharply increased (temporarily) the profits of the largest US corporations, especially the banks. But that extra money (paid for by further cuts in US federal public services and a big increase in government borrowing) is not going mainly into extra productive investment. It is being used to buy back corporate shares to boost the share price of companies and into extra dividend payments to shareholders.

S&P 500 companies have already announced about $167bn of new buyback authorisations this year, and analysts at JPMorgan predict that trend will accelerate this quarter as boardrooms digest the full scale of the tax cuts passed in December. Overall, US companies will buy back about $800bn of their stock this year, up from $525bn in 2017, and boost dividend payouts by about 10 per cent to a record $500bn. While US companies will lift their spending on investments, research and development by 11 per cent to more than $1tn this year, shareholder returns in the form of buybacks and dividends will grow by 21.6 per cent to nearly $1.2tn. The buyback spree will also lift the amount of profit companies make per share. S&P 500 companies are expected to report earnings growth of 17.1 per cent in the first quarter, which would the highest growth since the start of 2011, according to FactSet. That is up sharply from the rate of 11.3 per cent that was projected at the start of the year.

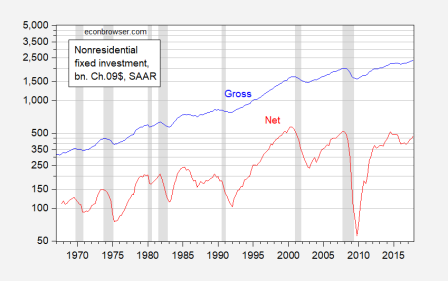

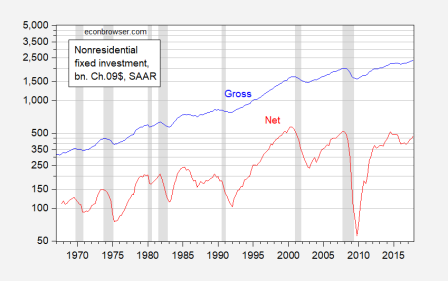

In contrast, US business investment in new plant, machinery and technology, while rising in gross amounts, is barely keeping pace with depreciation (wearing out) of existing fixed assets. Despite the recent acceleration in investment, net business investment has not re-attained levels achieved in 2014Q3 (let alone on the eve of the last recession).

I have argued before that business investment, not just in the US, but in most major economies remains low relative to before the Great Recession, ten years ago, for two main reasons: relatively low profitability and record high levels of debt. In a previous post, using data from the EU’s AMECO database, I showed that the rate of profit in most major economies remains below that of 2007 and even 1999, at least up to 2016.

There was a small recovery in profitability in Europe in 2017, but a further fall in the US, despite rising total profits.

In its latest reports, the IMF has pointed out that global debt has now reached record highs as central banks pumped credit into banks and financial institutions and households and corporations borrowed more at very low interest rates to either speculate in stock and bond markets or real estate. Governments also continued to rack up higher levels of public debt to fund bailouts to the financial institutions and cover rising budget deficits created by tax cuts and extra defence spending.

According to the IMF, global debt hit a new record high of $164 trillion in 2016, the equivalent of 225% of global GDP. Both private and public debt surged over the past decade. Of the $164 trillion, 63% is non-financial private sector debt (owed by households in mortgages and companies in bonds and loans), and 37% is public sector debt. Advanced economies have the most global debt. But, in the last ten years, emerging market economies have been responsible for most of the increase.

Debt-to-GDP ratios in advanced economies are at levels not seen since World War II. Public debt ratios have been increasing persistently over the past 50 years. In emerging market economies, public debt is at levels seen only during the 1980s’ debt crisis.

The US is still the largest and most important capitalist economy in the world. But it is steadily losing out relatively to the rising economic powers of Asia, particularly China. That is the driving force behind Trump’s protectionist crusade on trade and his huge cuts in corporate tax for American business. The tax cuts will lead to a significant rise in US federal debt over the coming years and that means higher interest costs that will suck up funding that could have been used to maintain public services and expand badly needed infrastructure. The IMF reckons that the annual US government deficit will go above $1trn in the next three years to reach 5% of GDP, taking the government debt level to 117% of US GDP then. According to the IMF, the US will be the only economy with a rising government debt ratio to GDP in that period.

Indeed, US imperialism continues to reveal its long-term vulnerability. The US now has a net investment liability with other economies in the world to the tune of 9.8% of world GDP. This compares with countries which are net creditors: Japan (3.9%), Northern Europe (6.4%) and China (2.3%). This US net liability measures the stock of investment and the amount of credit made by other countries into the US after deducting US investment and loans abroad. US imperialism is extracting more net value from other economies to fund its growth, but at the expense of becoming more dependent on ‘tribute’ rather than trade. The IMF forecasts that the US net liability to foreigners will reach 50% of its GDP by 2023, or 10.7% of world GDP. That compares with the combined liability of the exploited peripheral economies of the world of 7.8%. US imperialism gets away this because it is still the world’s largest economy, with the biggest financial sector, with the dollar as the world reserve currency and is the policeman of the world for imperialism.

As for the so-called emerging capitalist economies, the IMF points out that while foreign capital flows have remained robust in recent years, as the ‘global liquidity tide’ recedes with central banks raising interest rates, flows to emerging markets could decline by as much as $60 billion a year, equal to about a quarter of annual totals in 2010-17. “In such a scenario, less creditworthy borrowers may experience relatively larger outflows. Low-income countries may be affected, because more than 40 percent of them are at a high risk of debt distress.”

Falling profitability and rising debt (fictitious capital, to use Marx’s term) is a recipe for a nasty fall in global capitalism. As the IMF admitted “Looking ahead, the odds of a downturn remain elevated, and there’s even a small chance of a global economic contraction over the medium-term.”

At the end of last year, I made my annual forecast for the world economy in 2018. In that post, I recognised that I had not expected the relative pick-up in global growth in 2017 after the ‘bad years’ of 2015 and 2016. But I was not convinced that this ‘recovery’ meant that the Long Depression of low growth, investment and profitability (along with stagnant average household incomes) was over. I pointed out that IMF’s then projection global GDP growth was still less than the post-1965 trend of 3.8% growth and the expected gains over 2017-2018 followed an exceptionally weak recovery in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The IMF has raised its forecast to 3.9% for this year and next but it does not seem too confident that it will be achieved and after 2019, it expects a significant slowdown again.

Nevertheless, I had been forecasting a new global recession in 2018. I said then that “What seems to have happened is that there has been a short-term cyclical recovery from mid-2016, after a near global recession from the end of 2014-mid 2016. If the trough of this Kitchin (short-term) cycle was in mid-2016, the peak should be in 2018, with a swing down again after that.” The latest economic data in Q1 2018 suggest that growth has peaked globally. High debt and low profitability remain. Those fundamentals do not suggest any further upside – on the contrary.

The IMF hiked its forecast for global real GDP growth to 3.9% for this year and in 2019. This improvement from the poor levels of 2015 and 2016 is based on rising investment and a recovery in world trade (which now seems to be threatened). The major economies of world capitalism are doing better but the idiocies of protectionism in trade by the likes of Donald Trump are threatening that recovery. That seems to be the main worry.

But Obstfeld is worried about the high levels of global debt, in households, corporations and governments. With interest rates set to rise, as the US Fed and possibly other major central banks start to raise their policy rates, the cost of servicing record-high debt will rise. That threatens further investment in productive (value-creating) assets and also instability in financial markets.

There has already been a ‘correction’ in world stock markets of about 13% since the beginning of the year as financial speculators begin to worry about an international trade war and rising costs of debt. And that is despite the huge handouts in tax cuts for US corporations introduced by Trump. Those tax cuts have sharply increased (temporarily) the profits of the largest US corporations, especially the banks. But that extra money (paid for by further cuts in US federal public services and a big increase in government borrowing) is not going mainly into extra productive investment. It is being used to buy back corporate shares to boost the share price of companies and into extra dividend payments to shareholders.

S&P 500 companies have already announced about $167bn of new buyback authorisations this year, and analysts at JPMorgan predict that trend will accelerate this quarter as boardrooms digest the full scale of the tax cuts passed in December. Overall, US companies will buy back about $800bn of their stock this year, up from $525bn in 2017, and boost dividend payouts by about 10 per cent to a record $500bn. While US companies will lift their spending on investments, research and development by 11 per cent to more than $1tn this year, shareholder returns in the form of buybacks and dividends will grow by 21.6 per cent to nearly $1.2tn. The buyback spree will also lift the amount of profit companies make per share. S&P 500 companies are expected to report earnings growth of 17.1 per cent in the first quarter, which would the highest growth since the start of 2011, according to FactSet. That is up sharply from the rate of 11.3 per cent that was projected at the start of the year.

In contrast, US business investment in new plant, machinery and technology, while rising in gross amounts, is barely keeping pace with depreciation (wearing out) of existing fixed assets. Despite the recent acceleration in investment, net business investment has not re-attained levels achieved in 2014Q3 (let alone on the eve of the last recession).

I have argued before that business investment, not just in the US, but in most major economies remains low relative to before the Great Recession, ten years ago, for two main reasons: relatively low profitability and record high levels of debt. In a previous post, using data from the EU’s AMECO database, I showed that the rate of profit in most major economies remains below that of 2007 and even 1999, at least up to 2016.

There was a small recovery in profitability in Europe in 2017, but a further fall in the US, despite rising total profits.

In its latest reports, the IMF has pointed out that global debt has now reached record highs as central banks pumped credit into banks and financial institutions and households and corporations borrowed more at very low interest rates to either speculate in stock and bond markets or real estate. Governments also continued to rack up higher levels of public debt to fund bailouts to the financial institutions and cover rising budget deficits created by tax cuts and extra defence spending.

According to the IMF, global debt hit a new record high of $164 trillion in 2016, the equivalent of 225% of global GDP. Both private and public debt surged over the past decade. Of the $164 trillion, 63% is non-financial private sector debt (owed by households in mortgages and companies in bonds and loans), and 37% is public sector debt. Advanced economies have the most global debt. But, in the last ten years, emerging market economies have been responsible for most of the increase.

Debt-to-GDP ratios in advanced economies are at levels not seen since World War II. Public debt ratios have been increasing persistently over the past 50 years. In emerging market economies, public debt is at levels seen only during the 1980s’ debt crisis.

The US is still the largest and most important capitalist economy in the world. But it is steadily losing out relatively to the rising economic powers of Asia, particularly China. That is the driving force behind Trump’s protectionist crusade on trade and his huge cuts in corporate tax for American business. The tax cuts will lead to a significant rise in US federal debt over the coming years and that means higher interest costs that will suck up funding that could have been used to maintain public services and expand badly needed infrastructure. The IMF reckons that the annual US government deficit will go above $1trn in the next three years to reach 5% of GDP, taking the government debt level to 117% of US GDP then. According to the IMF, the US will be the only economy with a rising government debt ratio to GDP in that period.

Indeed, US imperialism continues to reveal its long-term vulnerability. The US now has a net investment liability with other economies in the world to the tune of 9.8% of world GDP. This compares with countries which are net creditors: Japan (3.9%), Northern Europe (6.4%) and China (2.3%). This US net liability measures the stock of investment and the amount of credit made by other countries into the US after deducting US investment and loans abroad. US imperialism is extracting more net value from other economies to fund its growth, but at the expense of becoming more dependent on ‘tribute’ rather than trade. The IMF forecasts that the US net liability to foreigners will reach 50% of its GDP by 2023, or 10.7% of world GDP. That compares with the combined liability of the exploited peripheral economies of the world of 7.8%. US imperialism gets away this because it is still the world’s largest economy, with the biggest financial sector, with the dollar as the world reserve currency and is the policeman of the world for imperialism.

As for the so-called emerging capitalist economies, the IMF points out that while foreign capital flows have remained robust in recent years, as the ‘global liquidity tide’ recedes with central banks raising interest rates, flows to emerging markets could decline by as much as $60 billion a year, equal to about a quarter of annual totals in 2010-17. “In such a scenario, less creditworthy borrowers may experience relatively larger outflows. Low-income countries may be affected, because more than 40 percent of them are at a high risk of debt distress.”

Falling profitability and rising debt (fictitious capital, to use Marx’s term) is a recipe for a nasty fall in global capitalism. As the IMF admitted “Looking ahead, the odds of a downturn remain elevated, and there’s even a small chance of a global economic contraction over the medium-term.”

At the end of last year, I made my annual forecast for the world economy in 2018. In that post, I recognised that I had not expected the relative pick-up in global growth in 2017 after the ‘bad years’ of 2015 and 2016. But I was not convinced that this ‘recovery’ meant that the Long Depression of low growth, investment and profitability (along with stagnant average household incomes) was over. I pointed out that IMF’s then projection global GDP growth was still less than the post-1965 trend of 3.8% growth and the expected gains over 2017-2018 followed an exceptionally weak recovery in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The IMF has raised its forecast to 3.9% for this year and next but it does not seem too confident that it will be achieved and after 2019, it expects a significant slowdown again.

Nevertheless, I had been forecasting a new global recession in 2018. I said then that “What seems to have happened is that there has been a short-term cyclical recovery from mid-2016, after a near global recession from the end of 2014-mid 2016. If the trough of this Kitchin (short-term) cycle was in mid-2016, the peak should be in 2018, with a swing down again after that.” The latest economic data in Q1 2018 suggest that growth has peaked globally. High debt and low profitability remain. Those fundamentals do not suggest any further upside – on the contrary.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario