Edward S. Herman died in November 2017, at the age of ninety-two. Because of his unassuming nature and genuine disinterest in claiming authorship for many of the ideas he generated, as long as they proliferated, his personal legacy may never do justice to his many contributions to those seeking a more just, humane, and sustainable world. I am but one of many people whose life he not only touched but whose life changed considerably because of his work and his counsel. Those fortunate enough to know Ed loved and respected him; he combined a powerful intellect with unimpeachable integrity and courage.

Although an accomplished economist during a long career as a professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Ed was first and foremost a person of the left, with a deep and abiding commitment to a peaceful and just world. His overriding concern with U.S. imperialism and militarism had crystallized with his opposition to the war in Vietnam. Beginning in the late 1960s and 1970s, Ed wrote a number of searing, detailed critiques of U.S. foreign policy, including three volumes with Noam Chomsky and one with Richard Du Boff.

Through this work, Ed continually came across the enormous discrepancy between actual developments around the world and their treatment in the U.S. news media. This led to his pioneering work in media criticism, which became a core component of his research and writing on global politics and U.S. foreign policy over the last forty years of his life, and for which he is best known. Routinely infuriated by the way the mainstream press spoonfed its audience the U.S. elite foreign policy consensus as unvarnished truth—even when transparently flawed and decontextualized, if not entirely bogus—Ed began developing a detailed critique of this coverage. As a graduate student and socialist living in Seattle in the 1980s, I was well aware of his work, but the incipient media critique he was writing as part of his analysis of U.S. foreign policy was still largely lost in the shuffle to an audience outside of an activist segment of the left.

That all changed when Ed teamed up with Noam Chomsky to write Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, published by André Schiffrin’s Pantheon Books in 1988. Chomsky at this point was writing and speaking a great deal about the media as well, so it was a fortunate pairing, and it produced arguably the most important work in news media criticism ever written.

Manufacturing Consent presented a series of paired case studies—each comprising a chapter—where the facts were largely the same, but in which U.S. interests were on opposite sides in the paired examples. For example, the U.S. news media coverage of the 1980 murder by the U.S.-backed El Salvador National Guard of four American Catholic missionaries, who were working with the poor, was paired with the coverage of the 1984 murder of the dissident priest Jerzy Popiełuszko by the Soviet-backed Polish communist government. In every case, the coverage was entirely sympathetic to victims seemingly allied with the United States, and entirely unsympathetic to those regarded as hostile to U.S. interests, like the Maryknoll Sisters. At every level of coverage, a double standard prevailed concerning the type of evidence considered “legitimate” and the assumptions about the motives of the various parties. The material, painstakingly gathered and presented in each case study after a thorough review of elite U.S. news media, was irrefutable.

I can make that last statement with some authority, because I taught the book for years, and I always sought out the best criticism of it from the mainstream. Often I would assign this criticism of Manufacturing Consent along with the book itself, to help students develop their own critique of Herman and Chomsky’s arguments. The mainstream criticism was disingenuous and unconvincing; even my most uncritical students could not disagree with the evidence or the conclusions in Manufacturing Consent. I suspect many of these students ended up doing what the news media and mainstream academics did; they simply ignored it and dismissed it categorically and hoped that by doing so they could make it go away.

But not all of them. The genius of Manufacturing Consent was that it opened an entirely new way of understanding the U.S. news media, not only for activists and people on the left, but also for more than one generation of students and young people trying to make sense of the news media. It introduced them to a new way of viewing the world from a critical perspective, and understanding the importance, possibility, and necessity of social change. There is no doubt that it is the most widely read and influential work on how to understand the U.S. news media. It remains so, and is more relevant than ever, three decades after its publication. It is not the final word on news media criticism, but the necessary starting point for successfully entering that world.

What distinguished Manufacturing Consent from other works of media criticism, however, was not the meticulous case studies. It was that the book systematically took on the question that hounded all left media critics: Is this a conspiracy theory of editors, reporters, owners, and advertisers to consciously doctor the news to suit elite interests? Framed that way, left criticism seems preposterous and unpersuasive. To this end, the book introduced the propaganda model, which explained how a series of five structural and ideological filters made editors and journalists largely oblivious to the compromises with elite interests they routinely made. To them it seemed natural. The propaganda model was largely Ed’s creation, and it kicked off the book in a powerful opening chapter.

Not surprisingly, Ed had a deep interest in cultivating an alternative left and progressive media. Over the years he supported innumerable left media outlets and progressive groups working in media criticism and activism, either with his labor or a timely donation. Having served on many boards for these groups, I can say with confidence that he was a hero to most of them, though he eschewed any publicity whatsoever for his contributions.

Ed had a particularly warm spot in his heart for

Monthly Review, calling it “my favorite journal.” He penned some

twenty articles for

MR over the last five decades. His last piece, “

Fake News on Russia and Other Official Enemies: The New York Times, 1917–2017,” was published in the July–August 2017 issue, and featured signature Herman analysis at its very best. In it, Ed demolished hypocritical U.S. media coverage of Russia, which, as he demonstrated, has depended not on actual evidence but mostly on whether the person in charge—be it Yeltsin or Putin—is a compliant pawn of the United States. It should be required reading, it is so relevant to the present time. Ed still threw his hundred-mile-per-hour fastball at age ninety-two!

I first met Ed through

MR, when I interviewed him in a piece for the magazine shortly after the publication of

Manufacturing Consent. We stayed in touch, and Ed constantly encouraged me with my work as my career was unfolding, calling me “Young Bob.” In 1995, Ed asked me to coauthor a book with him on global media. I leapt at the opportunity, and

The Global Media appeared in 1997. Simultaneously, I was beginning to write periodically for

MR, and I guest-edited the July–August 1996 issue on “

Capitalism and the Information Age,” along with John Bellamy Foster and Ellen Meiksins Wood. I thought any collection on communications would be incomplete without a contribution from Ed Herman. Because the propaganda model had in part attributed dominant journalistic double standards to the ideological filter of “anti-communism,” I asked Ed to explain how the propaganda model applied in a post-Cold War era. The piece that follows is what he produced.

We miss him already.

—Robert W. McChesney

In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (Pantheon, 1988) Noam Chomsky and I put forward a “propaganda model” as a framework for analyzing and understanding how the mainstream U.S. media work and why they perform as they do. We had long been impressed with the regularity with which the media operate within restricted assumptions, depend heavily and uncritically on elite information sources, and participate in propaganda campaigns helpful to elite interests. In trying to explain why they do this we looked for structural factors as the only possible root of systematic behavior and performance patterns.

The propaganda model was and is in distinct contrast to the prevailing mainstream explanations—both liberal and conservative—of media behavior and performance. These approaches downplay structural factors, generally presupposing their unimportance or positive impact because of the multiplicity of agents and thus competition and diversity. Liberal and conservative analysts emphasize journalistic conduct, public opinion, and news source initiatives as the main determining variables. The analysts are inconsistent in this regard, however. When they discuss media systems in communist or other authoritarian states, the idea that journalists or public opinion can override the power of those who own and control the media is dismissed as nonsense and even considered an apology for tyranny.

There is a distinct difference, too, between the political implications of the propaganda model and mainstream scholarship. If structural factors shape the broad contours of media performance, and if that performance is incompatible with a truly democratic political culture, then a basic change in media ownership, organization, and purpose is necessary for the achievement of genuine democracy. In mainstream analyses such a perspective is politically unacceptable, and its supportive arguments and evidence are rarely subject to debate.

In this article I will describe the propaganda model, address some of the criticism that has been leveled against it, and discuss how the model holds up nearly a decade after its publication.

1 I will also provide some examples of how the propaganda model can help explain the nature of media coverage of important political topics in the 1990s.

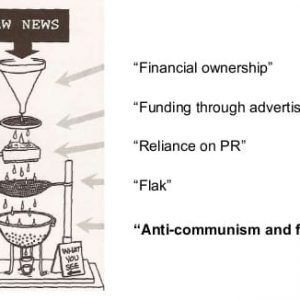

The Propaganda Model

What is the propaganda model and how does it work? The crucial structural factors derive from the fact that the dominant media are firmly imbedded in the market system. They are profit-seeking businesses, owned by very wealthy people (or other companies); they are funded largely by advertisers who are also profit-seeking entities, and who want their ads to appear in a supportive selling environment. The media are also dependent on government and major business firms as information sources, and both efficiency and political considerations, and frequently overlapping interests, cause a certain degree of solidarity to prevail among the government, major media, and other corporate businesses. Government and large non-media business firms are also best positioned (and sufficiently wealthy) to be able to pressure the media with threats of withdrawal of advertising or TV licenses, libel suits, and other direct and indirect modes of attack. The media are also constrained by the dominant ideology, which heavily featured anticommunism before and during the Cold War era, and was mobilized often to prevent the media from criticizing attacks on small states labelled communist.

These factors are linked together, reflecting the multileveled capability of powerful business and government entities and collectives (e.g., the Business Roundtable; U.S. Chamber of Commerce; industry lobbies and front groups) to exert power over the flow of information. We noted that the five factors involved—ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak, and anticommunist ideology—work as “filters” through which information must pass, and that individually and often in additive fashion they help shape media choices. We stressed that the filters work mainly by the independent action of many individuals and organizations; these frequently, but not always, share a common view of issues and similar interests. In short, the propaganda model describes a decentralized and non-conspiratorial market system of control and processing, although at times the government or one or more private actors may take initiatives and mobilize coordinated elite handling of an issue.

Propaganda campaigns can occur only when consistent with the interests of those controlling and managing the filters. For example, these managers all accepted the view that the Polish government’s crackdown on the Solidarity union in 1980–81 was extremely newsworthy and deserved severe condemnation; whereas the same interests did not find the Turkish military government’s equally brutal crackdown on trade unions in Turkey at about the same time to be newsworthy or reprehensible. In the latter case the U.S. government and business community liked the military government’s anticommunist stance and open door economic policy; and the crackdown on Turkish unions had the merit of weakening the left and keeping wages down. In the Polish case, propaganda points could be scored against a Soviet-supported government, and concern could be expressed for workers whose wages were not paid by Free World employers!

The fit of this dichotomization to corporate interests and anticommunist ideology is obvious.

We used the concepts of “worthy” and “unworthy” victims to describe this dichotomization, with a trace of irony, as the differential treatment was clearly related to political and economic advantage rather than anything like actual worth. In fact, the Polish trade unionists quickly ceased to be worthy when communism was overthrown and the workers were struggling against a western-oriented neoliberal regime. The travails of Polish workers now, like those of Turkish workers, do not pass through the propaganda model filters. They are both unworthy victims at this point.

We never claimed that the propaganda model explains everything or that it shows media omnipotence and complete effectiveness in manufacturing consent. It is a model of media behavior and performance, not media effects. We explicitly pointed to alternative media, grass roots information sources, and public skepticism about media veracity as important limits on media effectiveness in propaganda service, and we urged the support and more effective use of these alternatives. We have frequently pointed to the general public’s disagreement with the media and elite over the morality of the Vietnam War and the desirability of the assault on Nicaragua in the 1980s (among other matters). The power of the U.S. propaganda system lies in its ability to mobilize an elite consensus, to give the appearance of democratic consent, and to create enough confusion, misunderstanding, and apathy in the general population to allow elite programs to go forward. We also emphasized the fact that there are often differences within the elite that open up space for some debate and even occasional (but very rare) attacks on the intent, as well as the tactical means of achieving elite ends.

Although the propaganda model was generally well received on the left, some complained of an allegedly pessimistic thrust and implication of hopeless odds to be overcome. A closely related objection was its inapplicability to local conflicts where the possibility of effective resistance was greater. But the propaganda model does not suggest that local and even larger victories are impossible, especially where the elites are divided or have limited interest in an issue. For example, coverage of issues like gun control, school prayer, and abortion rights may well receive more varied treatment than, say, global trade, taxation, and economic policy. Moreover, well organized campaigns by labor, human rights, or environmental organizations fighting against abusive local businesses can sometimes elicit positive media coverage. In fact, we would like to think that the propaganda model even suggests where and how activists can best deploy their efforts to influence mainstream media coverage of issues.

The model does suggest that the mainstream media, as elite institutions, commonly frame news and allow debate only within the parameters of elite interests; and that where the elite is really concerned and unified, and/or where ordinary citizens are not aware of their own stake in an issue or are immobilized by effective propaganda, the media will serve elite interests uncompromisingly.

Mainstream Liberal and Academic ‘Left’ Critiques

Many liberals and a number of academic media analysts of the left did not like the propaganda model. Some of them found repugnant a wholesale condemnation of a system in which they played a respected role; for them it is a basically sound system, its inequalities of access regrettable but tolerable, its pluralism and competition effectively responding to consumer demands. In the postmodernist mode, global analyses and global solutions are rejected and derided; individual struggles and small victories are stressed, even by nominally leftist thinkers.

Many of the critiques displayed barely concealed anger; and in most the propaganda model was dismissed with a few superficial clichés (conspiratorial, simplistic, etc.) without minimal presentation of the model or subjecting it to the test of evidence. Let me discuss briefly some of the main criticisms.

Conspiracy theory. We explained in Manufacturing Consent that critical analyses like ours would inevitably elicit cries of conspiracy theory, and in a futile effort to prevent this we devoted several pages of the Preface to showing that the propaganda model is best described as a “guided market system,” and explicitly rejecting conspiracy. Mainstream critics still could not abandon the charge, partly because they knew that falsely accusing a radical critique of conspiracy theory would not cost them anything and partly because of their superficial assumption that since the media comprise thousands of “independent” journalists and companies any finding that they follow a “party line” serving the state must rest on an assumed conspiracy. (In fact it can result from a widespread gullible acceptance of official handouts, common internalized beliefs, fear of reprisal for critical analysis, etc.) The propaganda model explains media behavior and performance in structural terms, and intent is an unmeasurable red herring. All we know is that the media and journalists mislead in tandem—some no doubt internalize a propaganda line as true, some may know it is false, but the point is unknowable and irrelevant.

Failure to take account of media professionalism and objectivity. Communications professor Daniel C. Hallin argued that we failed to take account of the maturing of journalist professionalism, which he claimed to be “central to understanding how the media operate.” Hallin also stated that in protecting and rehabilitating the public sphere “professionalism is surely part of the answer.”

2

But professionalism and objectivity rules are fuzzy, flexible, and superficial manifestations of deeper power and control relationships. Professionalism arose in journalism in the years when the newspaper business was becoming less competitive and more dependent on advertising. Professionalism was not an antagonistic movement by the workers against the press owners, but was actively encouraged by many of the latter. It gave a badge of legitimacy to journalism, ostensibly assuring readers that the news would not be influenced by the biases of owners, advertisers, or the journalists themselves. In certain circumstances it has provided a degree of autonomy, but professionalism has also internalized some of the commercial values that media owners hold most dear, like relying on inexpensive official sources as the credible news source. As Ben Bagdikian has noted, professionalism has made journalists oblivious to the compromises with authority they are constantly making. Even Hallin acknowledges that professional journalism can allow something close to complete government control via sourcing domination.

While Hallin claimed that the propaganda model cannot explain the case of media coverage of the Central American wars of the 1980s, where there was considerable domestic hostility to the Reagan policies, in fact the propaganda model works extremely well there, whereas Hallin’s focus on “professionalism” fails abysmally. Hallin acknowledged that “the administration was able more often than not to prevail in the battle to determine the dominant frame of television coverage,” “the broad patterns in the framing of the story can be accounted for almost entirely by the evolution of policy and elite debate in Washington,” and “coherent statements of alternative visions of the world order and U.S. policy rarely appeared in the news.”

3This is exactly what the propaganda model would forecast. And if, as Hallin contended, a majority of the public opposed the elite view, what kind of “professionalism” allows a virtually complete suppression of the issues as the majority perceives them?

Hallin mentions a “nascent alternative perspective” in reporting on El Salvador—a “human rights” framework—that “never caught hold.” The propaganda model can explain why it never took hold; Hallin does not. With 700 journalists present at the Salvadoran election of 1982, allegedly “often skeptical” of election integrity, why did it yield a “public relations victory” for the administration and a major falsification of reality (as described in

Manufacturing Consent)?

4 Hallin did not explain this. He never mentioned the Office of Public Diplomacy or the firing of reporter Raymond Bonner and the work of the flak machines. He never explained the failure of the media to report even a tiny fraction of the crimes of the contras in Nicaragua and the death machines of El Salvador and Guatemala, in contrast with their inflation of Sandinista misdeeds and double standard in reporting on the Nicaraguan election of 1984. Given the elite divisions and public hostility to the Reagan policy, media subservience was phenomenal and arguably exceeded that which the propaganda model might have anticipated.

5

Failure to explain continued opposition and resistance. Both Hallin and historian Walter LaFeber (in a review in the New York Times) pointed to the continued opposition to Reagan’s Central America policy as somehow incompatible with the model. These critics failed to comprehend that the propaganda model is about how the media work, not how effective they are. By the logic of this form of criticism, as many Soviet citizens did not swallow the lines put forward by Pravda, this demonstrates that Pravda was not serving a state propaganda function.

Propaganda model too mechanical, functionalist, ignores existence of space, contestation, and interaction. This set of criticisms is at the heart of the negative reactions of the serious left-of-center media analysts such as Philip Schlesinger, James Curran, Peter Golding, Graham Murdoch, and John Eldridge, as well as of Hallin. Of these critics, only Schlesinger both summarizes the elements of our model and discusses our evidence. He acknowledges that the case studies make telling points, but in the end he finds ours “a highly deterministic vision of how the media operate coupled with a straightforward functionalist conception of ideology.”

6 Specifically, we failed to explain the weights to be given our five filters; we did not allow for external influences, nor did we offer a “thoroughgoing analysis of the ways in which economic dynamics operate to structure both the range and form of press presentations” (quoting Graham Murdoch); and while putting forward “a powerful effects model” we admit that the system is not all-powerful, which calls into question our determinism.

The criticism of the propaganda model for being deterministic ignores several important considerations. Any model involves deterministic elements, so that this is a straw person unless the critics also show that the system is not logically consistent, operates on false premises, or that the predictive power of the determining variables is poor. The critics often acknowledge that the case studies we present are powerful, but they do not show where the alleged determinism leads to error nor do they offer or point to alternative models that would do a better job.

7

The propaganda model is dealing with extraordinarily complex sets of events, and only claims to offer a broad framework of analysis that requires modification depending on many local and special factors, and may be entirely inapplicable in some cases. But if it offers insight in numerous important cases that have large effects and cumulative ideological force, it is defensible unless a better model is provided. Usually the critics wisely stick to generalities and offer no critical detail or alternative model; when they do provide alternatives, the results are not impressive.

8

The criticism of the propaganda model for functionalism is also dubious and the critics sometimes seem to call for more functionalism. The model does describe a system in which the media serve the elite, but by complex processes incorporated into the model as means whereby the powerful protect their interests naturally and without overt conspiracy. This would seem one of the propaganda model’s merits; it shows a dynamic and self-protecting system in operation. The same corporate community that influences the media through its power as owner, dominant funder (advertising), and a major news source also underwrites Accuracy in Media and the American Enterprise Institute to influence the media through harassment and the provision of “sound” experts. Critics of propaganda model functionalism like Eldridge and Schlesinger contradictorily point to the merit of analyses that focus on “how sources organize media strategies” to achieve their ends. Apparently it is admirable to analyze micro corporate strategies to influence the media, but to focus on global corporate efforts to influence the media—along with the complementary effects of thousands of local strategies—is illegitimate functionalism!

It is also untrue that the propaganda model implies no constraints on media owners/managers. We spell out the conditions affecting when the media will be relatively open or closed—mainly disagreements among the elite and the extent to which other groups in society are interested in, informed about, and organized to fight about issues. But the propaganda model does start from the premise that a critical political economy will put front and center the analysis of the locus of media control and the mechanisms by which the powerful are able to dominate the flow of messages and limit the space of contesting parties. The limits on their power are certainly important, but why should they get first place, except as a means of minimizing the power of the dominant interests, inflating the elements of contestation, and pretending that the marginalized have more strength than they really possess?

Enhanced Relevance of the Propaganda Model

The dramatic changes in the economy, communications industries, and politics over the past decade have tended to enhance the applicability of the propaganda model. The first two filters—ownership and advertising—have become ever more important. The decline of public broadcasting, the increase in corporate power and global reach, and the mergers and centralization of the media, have made bottom line considerations more controlling. The competition for serving advertisers has become more intense. Newsrooms have been more thoroughly incorporated into transnational corporate empires, with shrunken resources and even less management enthusiasm for investigative journalism that would challenge the structure of power. In short, the professional autonomy of journalists has been reduced.

Some argue that the Internet and the new communication technologies are breaking the corporate stranglehold on journalism and opening an unprecedented era of interactive democratic media. There is no evidence to support this view as regards journalism and mass communication. In fact, one could argue that the new technologies are exacerbating the problem. They permit media firms to shrink staff while achieving greater outputs and they make possible global distribution systems, thus reducing the number of media entities. Although the new technologies have great potential for democratic communication, left to the market there is little reason to expect the Internet to serve democratic ends.

The third and fourth filters—sourcing and flak—have also strengthened as mechanisms of elite influence. A reduction in the resources devoted to journalism means that those who subsidize the media by providing sources for copy gain greater leverage. Moreover, work by people like Alex Carey, John Stauber, and Sheldon Rampton has helped us see how the public relations industry has been able to manipulate press coverage of issues on behalf of corporate America. The PR industry understands how to use journalistic conventions to serve its own ends. Studies of news sources reveal that a significant proportion of news originates in the PR industry. There are, by one conservative count, 20,000 more PR agents working to doctor the news today than there are journalists writing it.

The fifth filter—anticommunist ideology—is possibly weakened by the collapse of the Soviet Union and global socialism, but this is easily offset by the greater ideological force of the belief in the “miracle of the market” (Reagan). There is now an almost religious faith in the market, at least among the elite, so that regardless of evidence, markets are assumed benevolent and non-market mechanisms are suspect. When the Soviet economy stagnated in the 1980s, it was attributed to the absence of markets; when capitalist Russia disintegrated in the 1990s it was because politicians and workers were not letting markets work their magic. Journalism has internalized this ideology. Adding it to the fifth filter, in a world where the global power of market institutions makes anything other than market options seem utopian, gives us an ideological package of immense strength.

The propaganda model applies exceedingly well to the media’s treatment of the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the subsequent Mexican crisis and meltdown of 1994-95. Once again there was a sharp split between the preferences of ordinary citizens and the elite and business community, with polls consistently showing substantial majorities opposed to NAFTA—and to the bailout of investors in Mexican securities—but the elite in favor. Media news coverage, selection of “experts,” and opinion columns were skewed accordingly; their judgment was that the benefits of NAFTA were obvious, agreed to by all qualified authorities, and that only demagogues and “special interests” were opposed. Meg Greenfield,

Washington Post Op Ed editor, explained the huge imbalance in her opinion column: “On the rare occasion when columnists of the left, right, and middle are all in agreement…I don’t believe it is right to create an artificial balance where none exists.”

9 But with a majority of the public opposing NAFTA, the pro-NAFTA unity among the pundits simply highlighted the huge elite bias of mainstream punditry. It may be worth noting that the transnational media corporations have a distinct self-interest in global trade agreements, as they are among their foremost beneficiaries.

The pro-corporate and anti-labor bias of the mainstream media was also evident in the editorial denunciations (both in the

New York Times and

Washington Post) of labor’s attempt to influence votes on NAFTA, with no comparable criticism of corporate or governmental (U.S. and Mexican) lobbying and PR. After having touted the puny labor and environmental protective side-agreements belatedly added to NAFTA as admirable, the media then failed to follow up on their enforcement and, in fact, when labor tried to use their provisions to prevent attacks on union organization in Mexico, the press ignored the case or derided it as labor “aggression.”

10 With the Mexican meltdown beginning in December 1994, the media were clear that NAFTA was not to blame, and in virtual lockstep they supported the Mexican (investor) bailout, despite poll reports of massive general public opposition. Experts and media repeatedly explained that the merit of NAFTA was that it had “locked Mexico in” so that it could not resort to controls to protect itself from severe deflation. They were oblivious to the profoundly undemocratic nature of this lock-in.

11

As is suggested by the treatment of NAFTA and labor’s right to participate in its debates, the propaganda model applies to domestic as well as foreign issues. Labor has been under siege in the United States for the past fifteen years, but you would hardly know this from the mainstream media. The decertification of unions, use of replacement workers, and long and debilitating strikes like that involving Caterpillar were treated in a very low key, and in a notable illustration of the applicability of the propaganda model, the long Pittston miners strike was accorded much less attention than the strike of miners in the Soviet Union.

12 For years the media found the evidence that the majority of ordinary citizens were doing badly in the New Economic Order to be of marginal interest; they “discovered” this issue only under the impetus of Pat Buchanan’s right-wing populist outcries.

The coverage of the “drug wars” is well explained by the propaganda model.

13 In the health insurance controversy of 1992–93, the media’s refusal to take the single-payer option seriously, despite apparent widespread public support and the effectiveness of the system in Canada, served well the interests of the insurance and medical service complex. The uncritical media reporting and commentary on the alleged urgency of fiscal restraint and a balanced budget in the years 1992–96 fit well the business community’s desire to reduce the social budget and weaken regulation, culminating in the Contract with America.

14 The applicability of the propaganda model in these and other cases seems clear.

Final Note

In retrospect, perhaps we should have made it clearer that the propaganda model was about media behavior and performance, with uncertain and variable effects. Maybe we should have spelled out in more detail the contesting forces both within and outside the media and the conditions under which these are likely to be influential. But we clearly made these points, and it is quite possible that nothing we could have done would have prevented our being labelled conspiracy theorists, rigid determinists, and deniers of the possibility that people can resist (even as we called for resistance).

The propaganda model still seems a very workable framework for analyzing and understanding the mainstream media—perhaps even more so than in 1988. As noted earlier in reference to Central America, it often surpasses expectations of media subservience to government propaganda. And we are still waiting for our critics to provide a better model.

Notes

- ↩Noam Chomsky analyzes some of these criticisms in his Necessary Illusions (Boston: South End, 1989), appendix l.

- ↩Daniel C. Hallin, We Keep America on Top of the World: Television Journalism and the Public Sphere (London: Routledge, 1994), 13, 4.

- ↩Hallin, We Keep America on Top of the World, 64, 74, 77.

- ↩Hallin, We Keep America on Top of the World, 72.

- ↩For compelling documentation on this extraordinary subservience, see Chomsky, Necessary Illusions, 197–261.

- ↩Philip Schlesinger, “From Production to Propaganda?” Media, Culture and Society 11, no. 3 (1989): 283–306.

- ↩It should be noted that the case studies in Manufacturing Consent are only a small proportion of those that Chomsky and I have done which support the analysis of the propaganda model. Special mention should be made of those covering the Middle East, Central America, and terrorism. See especially Chomsky’s Necessary Illusions, The Fateful Triangle (London: Pluto, 1983), and Pirates & Emperors (Montreal: Black Rose, 1987), and my The Real Terror Network (Boston: South End, 1982), and (with Gerry O’Sullivan) The Terrorism Industry (New York: Pantheon, 1989).

- ↩In fact, the only attempt to offer an alternative model was by Nicholas Lemann in the New Republic. For an analysis of this effort, see Chomsky, Necessary Illusions,145–48.

- ↩Howard Kurtz, “The NAFTA Pundit Pack,” Washington Post, November 19, 1993.

- ↩For a discussion see Edward Herman, “Labor Aggression in Mexico,” Lies of Our Times(December 1994): 6–7.

- ↩For discussions of the media treatment of NAFTA and the Mexican meltdown, see Thea Lee, “False Prophets: The Selling of NAFTA,” Economic Policy Institute, 1995; Edward Herman, “Mexican Meltdown: NAFTA and the Propaganda System,” Z (September 1995).

- ↩Jonathan Tasini, “Lost in the Margins: Labor and the Media,” EXTRA! (Summer 1990).

- ↩See Noam Chomsky, Deterring Democracy (London: Verso, 1991), 114–21.

- ↩“Health Care Reform: Not Journalistically Viable,” EXTRA! July–August 1993); John Canham-Clyne, “When ‘Both Sides’ Aren’t enough: The Restricted Debate over Health Care Reform,” EXTRA! January–February 1994).