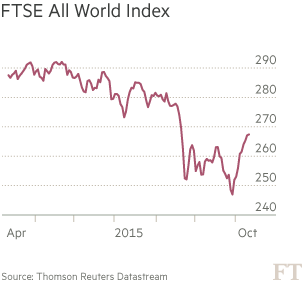

In the last few weeks, global stock and bond markets have been rallying after a period of sharp falls. The reason is clear.

The US Federal Reserve monetary policy chiefs have been talking down their plan of starting to hike interest rates this year. At their last meeting in September, the statement said that the planned increase in the Fed’s interest rates, which sets the floor for the cost of borrowing to spend or invest, may be postponed because the weakening situation in the global economy, particularly in the so-called emerging economies.

The slowdown in global growth has been well-documented in this blogin several posts. Now the expectation that the US Fed will not move ‘prematurely’ to drive up the cost of debt servicing in the rest of the world has helped to inspire a rally in the value of financial assets – for the moment.

But there has been no change in the underlying state of the global economy. On the contrary, on the ‘supply-side’ global industrial production remains very weak – from the US to Europe, to Japan and to China. ‘Domestic demand’ (ie spending by households and investment by companies) has been better, at least among households as the cost of credit cards and mortgages remains at all-time lows.

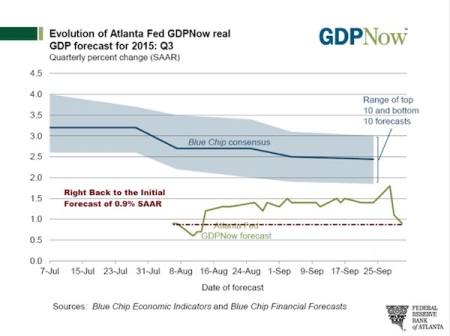

The US economy has been the leader among the advanced capitalist economies for economic growth since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. Even so, the US real GDP growth rate has averaged only 2.2% a year in six years, well below its trend average of 3.3% of the last 50 years, while growth per person is even lower. And projections for the third quarter just gone don’t justify the current stock market confidence. The Atlanta Federal Reserve produces the most accurate ‘high frequency’ forecast of US real GDP growth using a host of economic indicators. Currently, it expects the annual real GDP growth to be less than 1%.

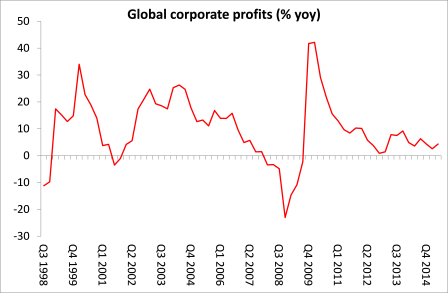

And while consumer demand has not slumped, what is showing signs of serious ‘wear and tear’ is profits. I have signalled the slowdown in global corporate profits before.

And the latest US company earnings results for the third quarter of 2015 (June to September), with only about 10% released so far, suggest an absolute fall in company profits for the top 500 US companies. The forecast is for a 4% contraction in earnings compared to last year in Q3 2015.

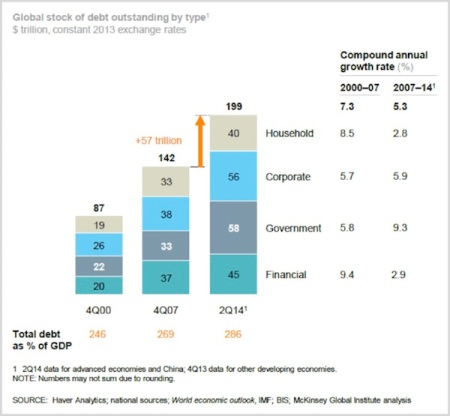

A fall in corporate earnings or profits in a slowing world economy is placing extra pressure on the ability to service debt built up, particularly by corporations in both the G7 and the emerging economies. Both the IMF and the world’s central bankers are worried that the build-up of debt that started well before the Great Recession has only got bigger since in most economies.

An obscure international body of central bankers, the Group of Thirty, recently presented a report warning that zero interest rates and money printing by major central banks were not working to revive economic growth and risked becoming semi-permanent measures. Instead, the flow of easy money has inflated asset prices like stocks and housing in many countries, even as they failed to stimulate economic growth. With growth estimates trending lower and easy money increasing company leverage, the spectre of a debt trap is now haunting advanced economies, the Group of Thirty said. It warned that the 40% decline in commodity prices could presage weaker growth and “debt deflation”.

The IMF in its latest report on global financial stability says the biggest risks to the global economy are now in emerging markets, where private companies have racked up considerable debt (up to $3 trillion) amid a fifth straight year of slowing growth. This unprecedented lending spree has come to an end with the plunge in prices for oil, minerals and other commodities that economists attribute to China’s slowdown. The risk is that shocks from bankruptcies in the developing world’s private sector could be amplified in global financial markets.

And it’s not just emerging economies that have a fragility with debt. Take the UK mining company, Glencore. It has $30 billion in debt. Charter Communications, after its acquisition of Time Warner Cable, will have as much as $67 billion in debt. And the combination of AB Inbev and SABMiller could create a brewer with over $100 billion in debt. US corporate debt is up by about $1 trillion in the seven years since the financial crisis. But corporate equity is up as well. Indeed, within the S&P 500 companies, the ratio of debt to equity has fallen from around 200% in 2009 to 100% today. So all is well?

Maybe not. While equity (stock market prices) has kept up with debt, corporate profits haven’t. At the end of second quarter, 62% of all companies had twice as much debt as cash flow from their operations, according to JPMorgan Chase. That’s up from 31% in the first quarter of 2006. The volume of corporate loans outstanding is now 14% higher than it was before the financial crisis. And, much like the situation in the run up to financial crisis, there’s been a boom in lending to risky borrowers. Last year, investors bought nearly $312 billion high yield bonds, often called junk bonds, up from $146 billion in 2006, which was the peak before the financial crisis.

According to McKinsey, at the end of 2007 the global stock of outstanding debt stood at $142 trillion. Then in 2008 the financial world fell apart. Less than seven years later, in mid-2014, there is anadditional $57 trillion in global debt, and the data this year is going to show that we’ve hit another record high. Debt as a percentage of GDP is even higher now than it was in 2007: 286% vs. 269%. Total debt grew at a 5.3% annual rate from 2007–14. But corporate debt grew even faster at 5.9% annually.

I have argued in many places that debt does matter under capitalism. Yes, credit is necessary to lubricate the wheels of capitalism and provide funds for investment where earnings cannot be raised in one production cycle. But debt must be repaid eventually and at least be serviced without resorting to raising even more debt to pay for old. And the ability to repay depends on profits. If profits do not match the debt servicing, capitalist companies head for bankruptcy. And the burden of debt weighs down on the ability or willingness of companies to invest. That leads to slow growth.

Of course, we are continually told by Keynesian economists that the problem with capitalism and the very weak economic recovery since 2009 is a ‘lack of demand’. Low profitability and the connection between profits and investment are ignored, while the claim that debt matters is dismissed. Most Marxist economists also adopt this view. For example, Chris Dillon, a Marxist economist blogger, seems to argue that ‘lack of demand’ is the chronic condition of capitalism that creates crises and stagnation in investment, in pretty much the same way as the Keynesians do. And like the Keynesians, he reckons that“sensible aggregate demand policies might suffice to overcome realization crises”. But unlike the Keynesians, for Dillon, capitalism cannot be reformed, because crises cannot be predicted and capitalist governments have no class interest in changing things.

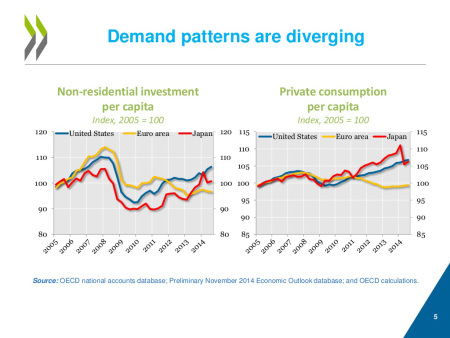

The argument that what is wrong with capitalism is a lack of consumer demand is refuted by the evidence of the last ten years: consumption generally strong and investment generally weak.

A lack of investment demand is more to the point. There is certainly not ‘over-investment’ relative to consumption, (the main cause of crises offered by Dillon). There is serious under-investment, caused, in my view, by low profitability relative to existing capital (including debt).

The debate continues within mainstream economics between debt and demand as the kernel of the capitalist problem and on what caused the Great Recession and what is causing the weak recovery. Kenneth Rogoff is the economic historian of financial crises and debt in modern economies.

Recently he has argued yet again that debt lies behind much of what has happened in the past seven years. He remarks that “Some argue that we are living in a world of deficient demand, doomed to decades of secular stagnation. Maybe. But another possibility is that the global economy is in the later stages of a debt “super cycle”, crushed under a burden accumulated over years of lax regulation and financial excess.” He rejects the modern version of Keynesian explanation, namely ‘secular stagnation’, promoted by the likes of Larry Summers and Brad de Long, caused by a chronic ‘lack of demand’ and thus the need to boost debt even more and raise government spending. “What if a diagnosis of secular stagnation is wrong? Then an ill-designed permanent rise in government spending might create the very disease it was intended to cure.” For Rogoff “most financial crises have their roots in a slowing economy that can no longer sustain excessive debt burdens.”

The Keynesians are not happy with Rogoff’s critique. They make the point that if governments try to reduce debt and ‘balance the books’, they will cut back demand and so lower growth in a downward cycle that it will be difficult to get out of. See this paper. So it seems that expanding credit can lead to a financial crisis but cutting it back can make things worse!

Perhaps, there is a middle way between not too little credit and not too much debt. Thus argues former head of Britain’s Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner. This was the agency that failed to spot the oncoming banking collapse in Britain in 2007. But no matter, Turner, in a new book, Between Debt and the Devil, tells us most credit is not needed for economic growth—but instead it drives real estate booms and busts and leads to financial crisis and depression. Banks need far more capital, real estate lending must be restricted, and we need to tackle inequality and mitigate the relentless rise of real estate prices. But sometimes we also need to monetize government debt and finance fiscal deficits with central-bank money. So government policy must straddle between the devil and the deep blue sea.

In a way, this is how top US mainstream economists Alan Blinder and Mark Zandi see it. They state that “crises are an inherent part of our financial system”. But, apparently, crises under capitalism are a necessary evil because “without them it is likely that the risk-taking necessary for strong long-term economic growth would be stymied.” The problem is that “when the good times roll, investors find it difficult to avoid getting caught up in the euphoria, to take on too much risk, and to saddle themselves with too much debt.”

Yes, indeed, it is a conundrum. But don’t worry about mass unemployment, bankruptcies and drops in living standards. “The worldwide financial crisis and global recession of 2007-2009 were the worst since the 1930s. With luck (sic!), we will not see their likes again for many decades. But we will see a variety of financial crises and recessions, and we should be better prepared for them than we were in 2007.” They argue that the ‘policy response’ by governments: cutting interest rates, printing money and a bit of government spending, eventually saved the day. Without that “we might have experienced Great Depression 2.0.”

The big problem for this comforting conclusion is that just as these economists congratulate themselves on avoiding another ‘Great Depression’ like the 1930s, it seems that the world economy is heading towards a new slump, with debt still at record levels and government policies of monetary easing exhausted.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario