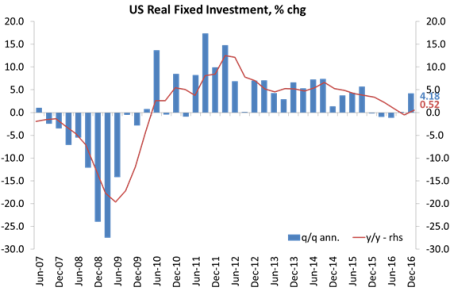

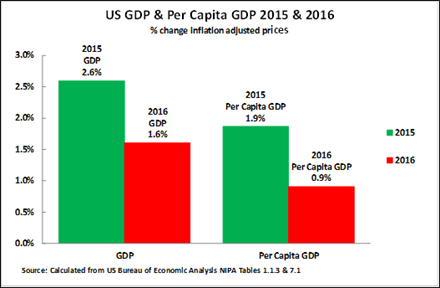

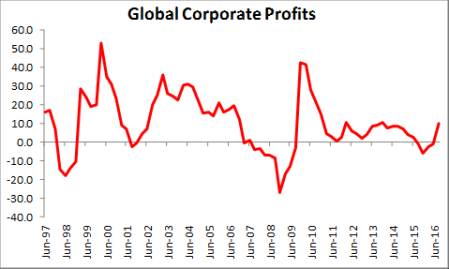

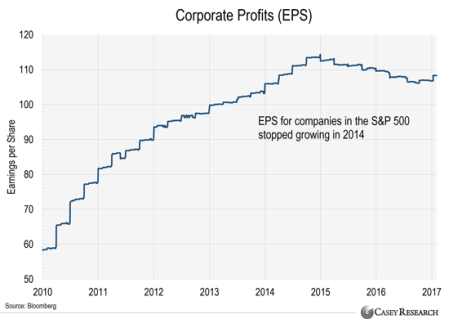

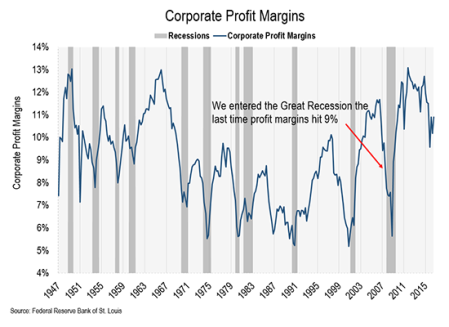

| The world’s stock markets continue to hit the roof, particularly the US markets which have reached all-time highs. ‘The Donald’ may dominate the headlines with his presidential decrees and tweets, but on the whole, financial investors remain optimistic. As I showed in a previous post, there is a growing consensus among economists and investors that things are looking up and the world economy is set for a sustained recovery. Take the latest forecasts from Gavyn Davies, former chief economist at Goldman Sachs and now running his own financial agency, Fulcrum. He comments “One of the most important questions for 2017 is whether this bout of reflation will continue. My answer, based partly on the latest results from the Fulcrum nowcast and inflation models, is that it will continue, at least compared to the sluggish rates of increase in nominal GDP since the Great Financial Crash.” Moreover “The nowcasts continue to report strong growth across the board, with world activity now expanding at a 4.2 per cent annualised rate Strong growth is especially apparent in the advanced economies, where the growth rate is now 3.0 per cent, a figure that is well above the long term trend of 1.8 per cent. Furthermore, activity growth is estimated to be above trend in all of the major advanced economies simultaneously: US (3.6 per cent), Eurozone (2.5 per cent), Japan (1.8 per cent) and the UK (2.5 per cent).” So it is looking good. However, as I did in my previous post, I must throw some cold water on this forecast for higher and sustained economic growth. Sustained trend growth does not depend on consumption; it does not depend on more spending by households on goods and services financed by more borrowing or induced by higher share prices. It depends on increased investment in production capacity leading to higher productivity growth. And that, in turn depends on better profits for the key corporate sector of an economy. And as yet, there is little sign of that. For example, in the data for the last quarter of 2016 for the US economy, any pickup in business investment was minimal. US real GDP figures show an annualised rise of 1.9%. So real growth in 2016 was just 1.6% compared to 2.6% in 2015 – the slowest rate since the end of the Great Recession. There was a bit more business investment after three quarters of decline. But business investment was still up only 0.3% yoy. The key sector of equipment investment was still falling by 3.6% yoy.  As a result, productivity growth (that’s the increase in output per worker), is stagnant, especially in the key productive sectors like manufacturing.  These are similar points to those made by John Ross in his latest post on the US economy, namely the myth of a strong economic recovery.  Well, it could be argued: that’s the past. As Gavyn Davies and others argue, things will be different this year. Even ‘post-Brexit’ Britain is likely to record reasonable growth of 2% this year, say the Bank of England and other agencies, contrary to their doomladen forecasts after the referendum last summer. But I say again, the key indicators are an increase in business investment and behind that, the driver of, an increase in corporate profits. The figures we have for the third quarter of 2016 (general the latest) suggest a mild recovery in global profits from the slowdown experienced since 2014. But it is not much to go on.  The overall trend in US corporate profits has been down for over two years. The graph below shows what has happened to earnings per share (EPS) for the top 500 companies in America.  And behind this decline lies a fall in the record highs achieved in corporate profit margins (i.e. the share of profits in total output) from as early as 2011 – in other words, corporate profits rose but even more slowly than corporate sales or total output. Some mainstream economists argue that this is good news because tighter margins will increase competition and reduce inequality. But this is nonsense, as I argued in Jacobin last year. I argued in that Jacobin piece, falling profits and profit margins herald a slump in investment and then a slump in production and employment. JP Morgan and other investment bank economists have made the same point. Corporate profit margins are still well above their historic average. In order for them to revert to their mean, they would have to fall to 9%, according to Casey Research. The last time profit margins sunk that low, the US economy entered the Great Recession of 2008-9.  |

And behind that situation is the level of corporate debt, something ignored by the likes of Gavyn Davies. As Austrian economist, William White puts it in a damning piece, “the question that all market observers ultimately have to answer today is whether the epic accumulation of global debt is sustainable. If it is not, as I believe, the next question is how to identify the signs indicating that excesses are becoming unsustainable and leading to breakage.”

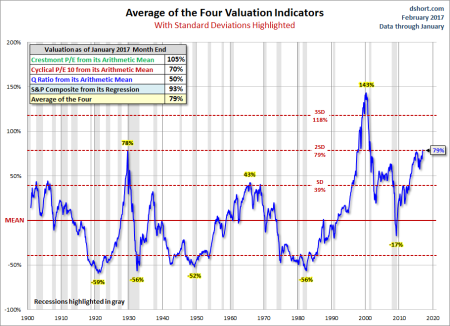

Michael Lewitt points out that stock markets “are chasing the highest valuations in history.” As the graph below shows, they still have some way to go to match the hi-tech bubble excess of 2000. But the US stock market is now at the same level of valuation as just before the 1929 crash.

And yet financial markets are not supported by strong corporate earnings and real GDP growth. According to Factset, estimated non- GAAP earnings growth for S&P companies in 2016 was a paltry +0.1% (and GAAP earnings growth was negative). Revenues were up roughly 2.0%. “Wall Street strategists trying to tempt investors into buying more stocks at these levels are playing with fire.” (Casey).

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario