Today, the global political and economic elite meet in Davos Switzerland under the auspices of the World Economic Forum (WEF). Every year the WEF has an annual meeting in the super exclusive ski resort of Davos, with the participation of 3,000 politicians, business leaders, economists, entrepreneurs, charity leaders and celebrities. For example, this year Chinese president Xi Jinping, South Africa’s Jacob Zuma and many of the economic mainstream gurus and banking officials are among the attendees. Xi Jinping will be the first Chinese president to attend Davos and will lead an unprecedented 80-strong delegation of business leaders, economists, academics and journalists. He will deliver the opening plenary address on Tuesday and use it to defend “cooperation and economic globalisation”.

US vice-president Joe Biden, China’s two richest men and London mayor Sadiq Khan will travel on private jets to nearby airports before transferring by helicopter to escape the traffic on the approach to the picturesque town. So many jets are expected that the Swiss government has opened up Dübendorf military airfield, an 85-mile helicopter flight away, to accommodate them. The increase in private jet flights – which each burn as much fuel in one hour as typical use of a car does in a year – comes as the WEF warns that climate change is the second most important global concern.

While the rich elite fly in on their private jets, extra hotel workers are being bussed in to serve the delegates, while packing into five a room in bunk beds. One of the main themes of Davos will be the rising inequality of income and wealth. So Davos itself is a microcosm.

At Davos’ super luxury hotel the Belvedere, there will be “specially recruited people just for mixing cocktails”, as well as baristas, cooks, waiters, doormen, chambermaids and receptionists to host world leaders, business people and celebrities, who this year include pop star Shakira and celebrity chef Jamie Oliver (worth $400m). Last year, a Silicon Valley tech company was reportedly charged £6,000 for a short meeting with the president of Estonia in a converted luggage room. The hotel has also previously flown in New England lobster and provided special Mexican food for a company that was meeting a Mexican politician.

Britain’s Theresa May will be the only G7 leader to attend this year’s summit as it clashes with Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th US president. Last year, former UK PM David Cameron partied tie-less with Bono, Leonardo DiCaprio and Kevin Spacey, at a lavish party hosted by Jack Ma, the founder of internet group Alibaba and China’s richest man with a $34.5bn (£28.5bn) fortune. Tony Blair also attended the Ma party last year.

Basic membership of the WEF and an entry ticket costs 68,000 Swiss francs (£55,400). To get access to all areas, corporations must pay to become Strategic Partners of the WEF, costing SFr600,000, which allows a CEO to bring up to four colleagues, or flunkies, along with them. They must still pay SFr18,000 each for tickets. Just 100 companies are able to become Strategic Partners; among them this year are Barclays, BT, BP, Facebook, Google and HSBC. The most exclusive invite in town is to an uber-glamorous party thrown jointly by Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska and British financier Nat Rothschild at the oligarch’s palatial chalet, a 15-minute chauffeur-driven car ride up the mountain from Davos. In previous years, Swiss police have reportedly been called to Deripaska’s home after complaints about the noise of his Cossack band. Deripaska’s parties have “endless streams of the finest champagne, vodka, and Russian caviar amidst dancing Cossacks and beautiful Russian models.”

The official theme of this year’s forum is “responsive and responsible leadership”! That hints at the concerns of global capitalism’s elite: they need to be ‘responsive’ to the popular reaction to globalisation and the failure of capitalism to deliver prosperity since the end of the Great Recession and they also need to be ‘responsible’ in their policies and actions – a subtle appeal to the newly inaugurated Donald Trump as US president or Erdogan in Turkey, Zuma in South Africa, Putin in Russia and Xi in China.

The WEF has been the standard bearer of the positives from ‘globalisation’, new technology, free markets, ‘Western democracy’ and ‘responsible’ leadership. Trump and other leaders of global and regional powers now seem to threaten that enterprise. But Trump is the result of the failure of the WEF project itself i.e. global capitalist ‘progress’.

In my book, The Long Depression, in the final chapter I raised three big challenges for the capitalist mode of production over the next generation: rising inequality and slowing productivity; the rise of the robots and AI; and global warming and climate change. And these issues are taken up in this year’s WEF report entitled The Global Risks Report. The WEF report cites five challenges for capitalsim: 1 Rising Income and wealth disparity; 2 Changing climate; 3 Increasing polarization of societies; 4 Rising cyber dependency and 5 Ageing population.

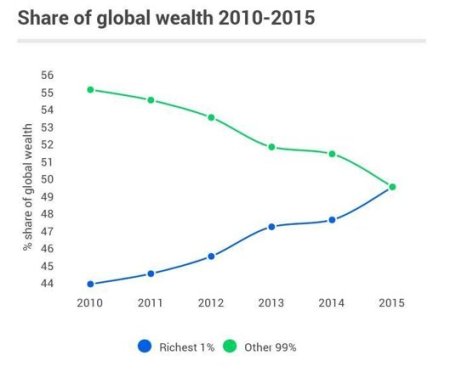

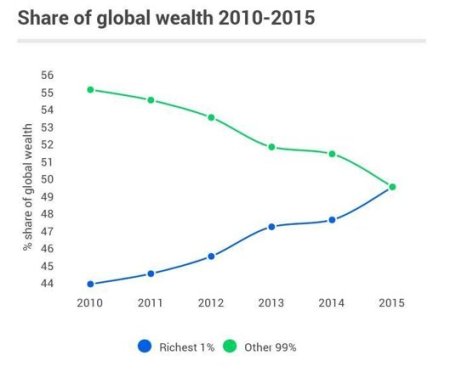

The report points out that while, globally, inequality between countries has been “decreasing at an accelerating pace over the past 30 years”, within countries, since the 1980s the share of income going to the top 1% has increased in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland and Australia (although not in Germany, Japan, France, Sweden, Denmark or the Netherlands). Actually, as I have shown in recent posts, global inequality (between countries) has only decline because of the huge rise in incomes per head in China. Excluding, there has been little improvement, with many lower income countries having worsening inequality. And as the WEF says, the slow pace of economic recovery since 2008 has “intensified local income disparities with a more dramatic impact on many households than aggregate national income data would suggest.”

The latest measures of inequality of incomes and wealth as presented by Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, Daniel Zucman and recently deceased Tony Atkinson, are truly shocking, with no sign of any reduction in inequality in the US, in particular.

Since the global financial crisis the incomes of the top 1% in the US grew by more than 31%, compared with less than 0.5% for the remaining 99% of the population, with 540 million young people across 25 advanced economies facing the prospect of growing up to be poorer than their parents. And to coincide with Davos, Oxfam, using the data compiled for the annual Credit Suisse wealth report finds that the world’s eight richest individuals have as much wealth as the 3.6bn people who make up the poorest half of the world!

In my blog and , I discuss the reasons for this sharp increase in inequality. Inequality is a feature of all class societies but under capitalism it will vary according to the balance of power in the class struggle between labour and capital. The WEF report likes to think that the cause is the differential of skills between those who are better educated and therefore can obtain higher wages. But research has shown this to be nonsense. The real disparity comes when capital can usurp a greater proportion of value created in capitalist production. Increased profitability, lower corporate taxes and booming stock and property markets since the 1980s have shifted up incomes from capital compared to wages, particularly for the top echelons in corporations.

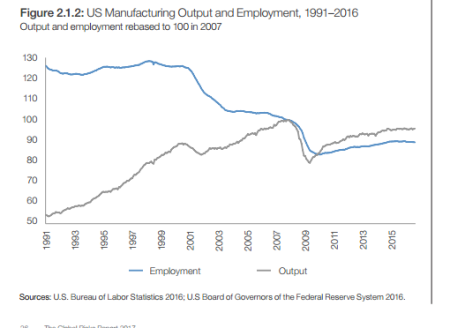

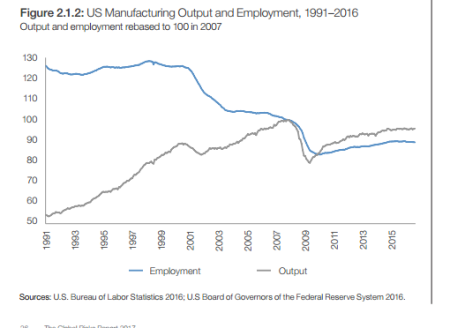

And then there is the impact of ‘capital bias’ in capitalist production that I have referred to before. According to the economists Michael Hicks and Srikant Devaraj, 86% of manufacturing job losses in the US between 1997 and 2007 were the result of rising productivity, compared to less than 14% lost because of trade.

“Most assessments suggest that technology’s disruptive effect on labour markets will accelerate across non-manufacturing sectors in the years ahead, as rapid advances in robotics, sensors and machine learning enable capital to replace labour in an expanding range of service-sector job. A frequently cited 2013 Oxford Martin School study has suggested that 47% of US jobs were at high risk from automation and in 2015, a McKinsey study concluded that 45% of the activities that workers do today could already be automated if companies choose to do so.” (WEF).

Technological change is shifting the distribution of income from labour to capital: according to the OECD, up to 80% of the decline in labour’s share of national income between 1990 and 2007 was the result of the impact of technology. While at a global level, however, many people are being left behind altogether: more than 4 billion people still lack access to the internet, and more than 1.2 billion people are without even electricity.

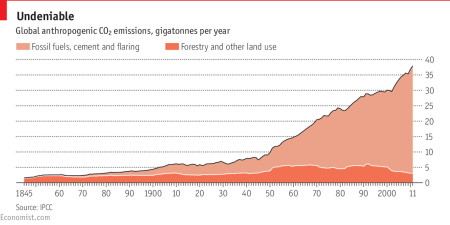

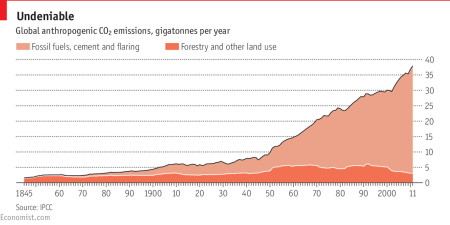

In my book, I cite the next challenge for capitalism is climate change from global warming. The WEF report does too. There are a growing “cluster of interconnected environment-related risks – including extreme weather events, climate change and water crises” .Global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are growing, currently by about 52 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year. Last year was the warmest on the instrumental record according to provisional analysis by the World Meteorological Organisation. It was the first time the global average temperature was 1 degree Celsius or more above the 1880–1999 average. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, each of the eight months from January through August 2016 were the warmest those months have been in the whole 137 year record.

As warming increases, impacts grow. The Arctic sea ice had a record melt in 2016 and the Great Barrier Reef had an unprecedented coral bleaching event, affecting over 700 kilometres of the northern reef. The latest analysis by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that, on average, 21.5 million people have been displaced by climate- or weather-related events each year since 2008,59 and the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) reports that close to 1 billion people were affected by natural disasters in 2015.

The Emissions Gap Report 2016 from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) shows that even if countries deliver on the commitments – known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – that they made in Paris, the world will still warm by 3.0 to 3.2°C. To keep global warming to within 2°C and limit the risk of dangerous climate change, the world will need to reduce emissions by 40% to 70% by 2050 and eliminate them altogether by 2100.

The World Bank forecasts that water stress could cause extreme societal stress in regions such as the Middle East and the Sahel, where the economic impact of water scarcity could put at risk 6% of GDP by 2050. The Bank also forecasts that water availability in cities could decline by as much as two thirds by 2050, as a result of climate change and competition from energy generation and agriculture. The Indian government advised that at least 330 million people were affected by drought in 2016. The confluence of risks around water scarcity, climate change, extreme weather events and involuntary migration remains a potent cocktail and a “risk multiplier”, especially in the world economy’s more fragile environmental and political contexts.

The third big challenge cited by the WEF is restoring global economic growth. The report points out that permanently diminished growth translates into permanently lower living standards: with 5% annual growth, it takes just 14 years to double a country’s GDP; with 3% growth, it takes 24 years. “If our current stagnation persists, our children and grandchildren might be worse off than their predecessors. Even without today’s technologically driven structural unemployment, the global economy would have to create billions of jobs to accommodate a growing population, which is forecast to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, from 7.4 billion today.”

So the WEF report highlights a whole batch of problems ahead for the stability and success of global capitalism. And what are the answers for a ‘responsive and responsible’ global leadership gathering in Davos? Capitalism must be preserved, of course, but it will necessary “to reform market capitalism and to restore the compact between business and society.”

But having said that globalisation is failing in its report, the WEF then says that the way forward is really more of the same. “Free markets and globalization have improved living standards and lifted people out of poverty for decades. But their structural flaws – myopic short-termism, increasing wealth inequality, and cronyism – have fueled the political backlash of recent years, in turn highlighting the need to create permanent structures for balancing economic incentives with social wellbeing.”

Thus the WEF report calls on the rich elite “to be responsive to the demands of the people who have entrusted them to lead, while also providing a vision and a way forward, so that people can imagine a better future.” And how to do this? “Leaders will have to build a dynamic, inclusive multi-stakeholder global-governance system…the way forward is to make sure that globalization is benefiting everyone.”

Reducing inequality and poverty, boosting productivity and growth through new technology while preserving jobs and raising incomes; reducing gas emissions into the atmosphere to avoid global catastrophes, while preserving and reforming capitalism through global cooperation from Trump in the US, Xi Ping in China, Putin in Russia and Brexit Britain and the European Union. Hmm…

US vice-president Joe Biden, China’s two richest men and London mayor Sadiq Khan will travel on private jets to nearby airports before transferring by helicopter to escape the traffic on the approach to the picturesque town. So many jets are expected that the Swiss government has opened up Dübendorf military airfield, an 85-mile helicopter flight away, to accommodate them. The increase in private jet flights – which each burn as much fuel in one hour as typical use of a car does in a year – comes as the WEF warns that climate change is the second most important global concern.

While the rich elite fly in on their private jets, extra hotel workers are being bussed in to serve the delegates, while packing into five a room in bunk beds. One of the main themes of Davos will be the rising inequality of income and wealth. So Davos itself is a microcosm.

At Davos’ super luxury hotel the Belvedere, there will be “specially recruited people just for mixing cocktails”, as well as baristas, cooks, waiters, doormen, chambermaids and receptionists to host world leaders, business people and celebrities, who this year include pop star Shakira and celebrity chef Jamie Oliver (worth $400m). Last year, a Silicon Valley tech company was reportedly charged £6,000 for a short meeting with the president of Estonia in a converted luggage room. The hotel has also previously flown in New England lobster and provided special Mexican food for a company that was meeting a Mexican politician.

Britain’s Theresa May will be the only G7 leader to attend this year’s summit as it clashes with Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th US president. Last year, former UK PM David Cameron partied tie-less with Bono, Leonardo DiCaprio and Kevin Spacey, at a lavish party hosted by Jack Ma, the founder of internet group Alibaba and China’s richest man with a $34.5bn (£28.5bn) fortune. Tony Blair also attended the Ma party last year.

Basic membership of the WEF and an entry ticket costs 68,000 Swiss francs (£55,400). To get access to all areas, corporations must pay to become Strategic Partners of the WEF, costing SFr600,000, which allows a CEO to bring up to four colleagues, or flunkies, along with them. They must still pay SFr18,000 each for tickets. Just 100 companies are able to become Strategic Partners; among them this year are Barclays, BT, BP, Facebook, Google and HSBC. The most exclusive invite in town is to an uber-glamorous party thrown jointly by Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska and British financier Nat Rothschild at the oligarch’s palatial chalet, a 15-minute chauffeur-driven car ride up the mountain from Davos. In previous years, Swiss police have reportedly been called to Deripaska’s home after complaints about the noise of his Cossack band. Deripaska’s parties have “endless streams of the finest champagne, vodka, and Russian caviar amidst dancing Cossacks and beautiful Russian models.”

The official theme of this year’s forum is “responsive and responsible leadership”! That hints at the concerns of global capitalism’s elite: they need to be ‘responsive’ to the popular reaction to globalisation and the failure of capitalism to deliver prosperity since the end of the Great Recession and they also need to be ‘responsible’ in their policies and actions – a subtle appeal to the newly inaugurated Donald Trump as US president or Erdogan in Turkey, Zuma in South Africa, Putin in Russia and Xi in China.

The WEF has been the standard bearer of the positives from ‘globalisation’, new technology, free markets, ‘Western democracy’ and ‘responsible’ leadership. Trump and other leaders of global and regional powers now seem to threaten that enterprise. But Trump is the result of the failure of the WEF project itself i.e. global capitalist ‘progress’.

In my book, The Long Depression, in the final chapter I raised three big challenges for the capitalist mode of production over the next generation: rising inequality and slowing productivity; the rise of the robots and AI; and global warming and climate change. And these issues are taken up in this year’s WEF report entitled The Global Risks Report. The WEF report cites five challenges for capitalsim: 1 Rising Income and wealth disparity; 2 Changing climate; 3 Increasing polarization of societies; 4 Rising cyber dependency and 5 Ageing population.

The report points out that while, globally, inequality between countries has been “decreasing at an accelerating pace over the past 30 years”, within countries, since the 1980s the share of income going to the top 1% has increased in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Ireland and Australia (although not in Germany, Japan, France, Sweden, Denmark or the Netherlands). Actually, as I have shown in recent posts, global inequality (between countries) has only decline because of the huge rise in incomes per head in China. Excluding, there has been little improvement, with many lower income countries having worsening inequality. And as the WEF says, the slow pace of economic recovery since 2008 has “intensified local income disparities with a more dramatic impact on many households than aggregate national income data would suggest.”

The latest measures of inequality of incomes and wealth as presented by Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, Daniel Zucman and recently deceased Tony Atkinson, are truly shocking, with no sign of any reduction in inequality in the US, in particular.

Since the global financial crisis the incomes of the top 1% in the US grew by more than 31%, compared with less than 0.5% for the remaining 99% of the population, with 540 million young people across 25 advanced economies facing the prospect of growing up to be poorer than their parents. And to coincide with Davos, Oxfam, using the data compiled for the annual Credit Suisse wealth report finds that the world’s eight richest individuals have as much wealth as the 3.6bn people who make up the poorest half of the world!

In my blog and , I discuss the reasons for this sharp increase in inequality. Inequality is a feature of all class societies but under capitalism it will vary according to the balance of power in the class struggle between labour and capital. The WEF report likes to think that the cause is the differential of skills between those who are better educated and therefore can obtain higher wages. But research has shown this to be nonsense. The real disparity comes when capital can usurp a greater proportion of value created in capitalist production. Increased profitability, lower corporate taxes and booming stock and property markets since the 1980s have shifted up incomes from capital compared to wages, particularly for the top echelons in corporations.

And then there is the impact of ‘capital bias’ in capitalist production that I have referred to before. According to the economists Michael Hicks and Srikant Devaraj, 86% of manufacturing job losses in the US between 1997 and 2007 were the result of rising productivity, compared to less than 14% lost because of trade.

“Most assessments suggest that technology’s disruptive effect on labour markets will accelerate across non-manufacturing sectors in the years ahead, as rapid advances in robotics, sensors and machine learning enable capital to replace labour in an expanding range of service-sector job. A frequently cited 2013 Oxford Martin School study has suggested that 47% of US jobs were at high risk from automation and in 2015, a McKinsey study concluded that 45% of the activities that workers do today could already be automated if companies choose to do so.” (WEF).

Technological change is shifting the distribution of income from labour to capital: according to the OECD, up to 80% of the decline in labour’s share of national income between 1990 and 2007 was the result of the impact of technology. While at a global level, however, many people are being left behind altogether: more than 4 billion people still lack access to the internet, and more than 1.2 billion people are without even electricity.

In my book, I cite the next challenge for capitalism is climate change from global warming. The WEF report does too. There are a growing “cluster of interconnected environment-related risks – including extreme weather events, climate change and water crises” .Global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are growing, currently by about 52 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year. Last year was the warmest on the instrumental record according to provisional analysis by the World Meteorological Organisation. It was the first time the global average temperature was 1 degree Celsius or more above the 1880–1999 average. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, each of the eight months from January through August 2016 were the warmest those months have been in the whole 137 year record.

As warming increases, impacts grow. The Arctic sea ice had a record melt in 2016 and the Great Barrier Reef had an unprecedented coral bleaching event, affecting over 700 kilometres of the northern reef. The latest analysis by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that, on average, 21.5 million people have been displaced by climate- or weather-related events each year since 2008,59 and the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) reports that close to 1 billion people were affected by natural disasters in 2015.

The Emissions Gap Report 2016 from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) shows that even if countries deliver on the commitments – known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – that they made in Paris, the world will still warm by 3.0 to 3.2°C. To keep global warming to within 2°C and limit the risk of dangerous climate change, the world will need to reduce emissions by 40% to 70% by 2050 and eliminate them altogether by 2100.

The World Bank forecasts that water stress could cause extreme societal stress in regions such as the Middle East and the Sahel, where the economic impact of water scarcity could put at risk 6% of GDP by 2050. The Bank also forecasts that water availability in cities could decline by as much as two thirds by 2050, as a result of climate change and competition from energy generation and agriculture. The Indian government advised that at least 330 million people were affected by drought in 2016. The confluence of risks around water scarcity, climate change, extreme weather events and involuntary migration remains a potent cocktail and a “risk multiplier”, especially in the world economy’s more fragile environmental and political contexts.

The third big challenge cited by the WEF is restoring global economic growth. The report points out that permanently diminished growth translates into permanently lower living standards: with 5% annual growth, it takes just 14 years to double a country’s GDP; with 3% growth, it takes 24 years. “If our current stagnation persists, our children and grandchildren might be worse off than their predecessors. Even without today’s technologically driven structural unemployment, the global economy would have to create billions of jobs to accommodate a growing population, which is forecast to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, from 7.4 billion today.”

So the WEF report highlights a whole batch of problems ahead for the stability and success of global capitalism. And what are the answers for a ‘responsive and responsible’ global leadership gathering in Davos? Capitalism must be preserved, of course, but it will necessary “to reform market capitalism and to restore the compact between business and society.”

But having said that globalisation is failing in its report, the WEF then says that the way forward is really more of the same. “Free markets and globalization have improved living standards and lifted people out of poverty for decades. But their structural flaws – myopic short-termism, increasing wealth inequality, and cronyism – have fueled the political backlash of recent years, in turn highlighting the need to create permanent structures for balancing economic incentives with social wellbeing.”

Thus the WEF report calls on the rich elite “to be responsive to the demands of the people who have entrusted them to lead, while also providing a vision and a way forward, so that people can imagine a better future.” And how to do this? “Leaders will have to build a dynamic, inclusive multi-stakeholder global-governance system…the way forward is to make sure that globalization is benefiting everyone.”

Reducing inequality and poverty, boosting productivity and growth through new technology while preserving jobs and raising incomes; reducing gas emissions into the atmosphere to avoid global catastrophes, while preserving and reforming capitalism through global cooperation from Trump in the US, Xi Ping in China, Putin in Russia and Brexit Britain and the European Union. Hmm…

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario