The Marxist theory of economic crises in capitalism – part two

December 29, 2015

In the first part of this double post, I dealt with whether Marx had a coherent theory of crises or not. I reckoned that Marx’s theory was based on his law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and that this law was realistic and coherent. I also argued that Marx did not dispense with this law in his later works that some have claimed and it remains the best and most compelling theory of regular and recurrent economic crises in capitalism. In this second part, I shall provide some empirical evidence from modern capitalist economies to support this view. This completes what is really just a short essay on Marxist economic crisis theory – as I see it – with much left out.

Does Marx’s law fit the facts?

Some Marxist critics of Marx’s law of profitability reckon that the law cannot be empirically proven or refuted because official statistics cannot be used to show Marx’s law in operation. But there are plenty of studies by Marxist economists that show otherwise. The key tests of the validity of the law in modern capitalist economies would be to show whether 1) the rate of profit falls over time as the organic composition of capital rises; 2) the rate of profit rises when the organic composition falls or when the rate of surplus value rises faster than the organic composition of capital; 3) the rate of profit rises, if there is sharp fall in the organic composition of capital as in a slump. These would be the empirical tests and there is plenty of empirical evidence for the US and world economy to show that the answer is yes to all these questions.

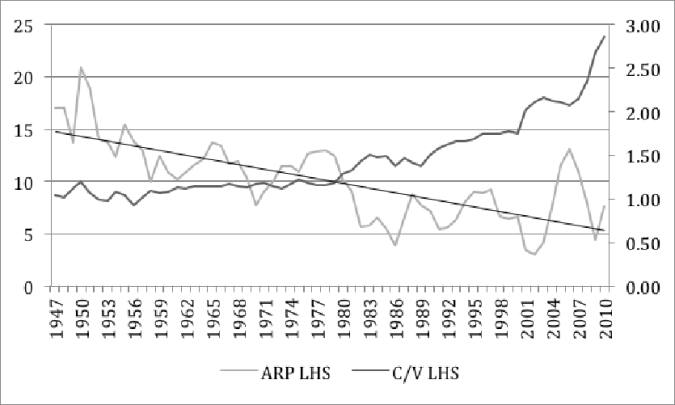

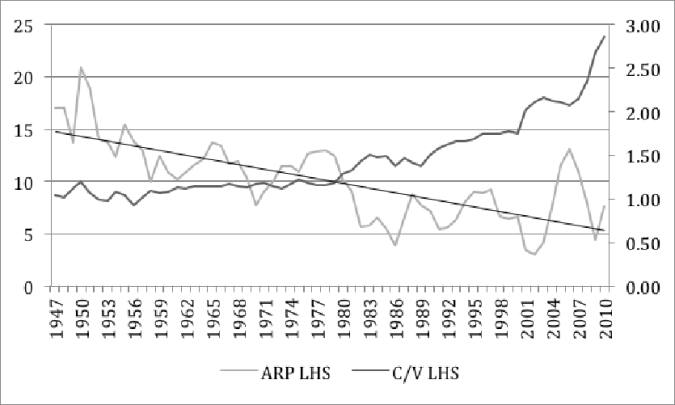

For example, Basu and Manolakos applied econometric analysis to the US economy between 1948 and 2007 and found that there was a secular tendency for the rate of profit to fall with a measurable decline of about 0.3 percent a year “after controlling for counter-tendencies.” In my work on the US rate of profit, I also found an average decline of 0.4 percent a year through 2009. And here is a figure by G Carchedi for the rise in the organic composition of capital (OCC) in the industrial sector of the US since 1947 versus the average rate of profit (ARP). It tells the same story.

US ARP and OCC (i.e. C/V)

There is a clear inverse correlation between a rising organic composition of capital and a falling rate of profit.

Can Marx’s law explain crises?

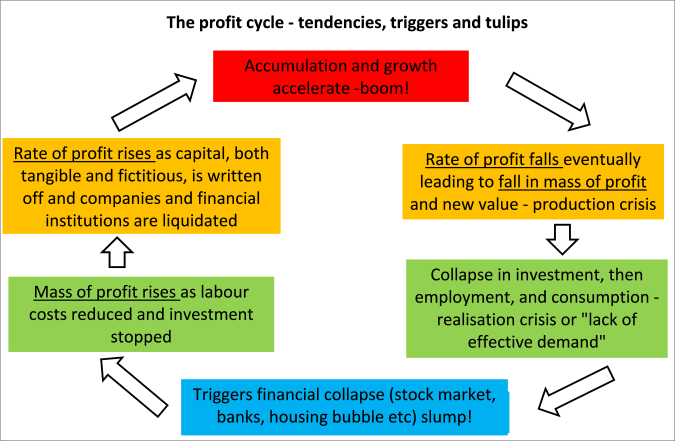

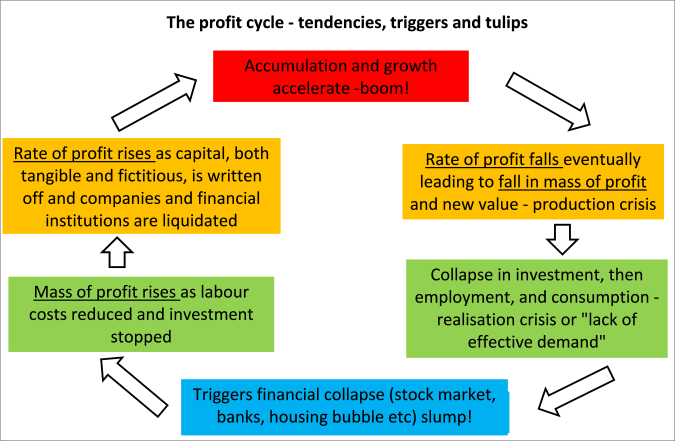

How does Marx’s law of profitability work as an explanation and forecast of slumps in capitalist economies? The law leads to a clear causal connection to regular and recurrent crises (slumps). It runs from falling profitability to falling profits to falling investment to falling employment and incomes. A bottom is reached when there is sufficient destruction of capital values (the writing off technology, the bankruptcy of companies, a reduction in wage costs) to raise profits and then profitability. Then rising profitability leads to rising investment again. The cycle of boom recommences and the whole ‘crap’ starts again, to use Marx’s colourful phrase. There is a cycle of profit alongside the long-term tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

The evidence of this causality between profit and investment is available. Jose Tapia Granados, using regression analysis, finds that, over 251 quarters of US economic activity from 1947, profits started declining long before investment did and that pre-tax profits can explain 44% of all movement in investment, while there is no evidence that investment can explain any movement in profits. I find a higher ‘Granger causality’ of 60% from annual changes in profit and investment (unpublished) and a correlation of 0.67 for the period since 2000. And see this by G Carchedi (Carchedi Presentation).

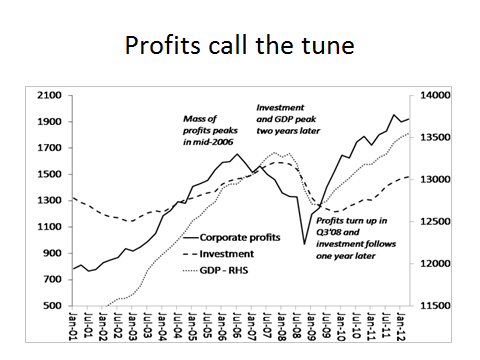

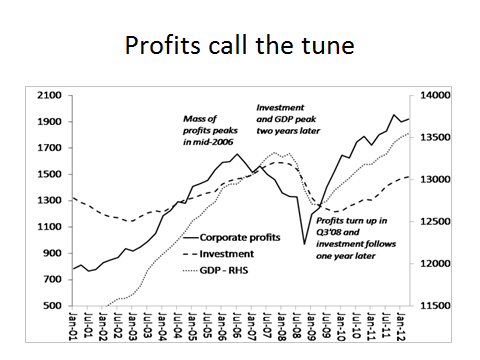

In the period leading up to the Great Recession 2008-9, we can see the causality visually for US profits, investment and real GDP in the graphic below. The mass of US corporate profit peaks in mid-2006, investment and GDP follows two years later. Profits turn back up in late 2008 and investment follows one year later.

There are two basic regularities shown by the data: that a change in profits tends to be followed next year by a change in investment in the same direction; and that a change in investment is usually followed in a few years by changes in profits in the opposite direction. Thus we have a cycle. From these results, the “regularity” of the business cycle, and the fact that profitability stagnated in 2013 and declined in 2014 (and now the mass of profits in 2015) after growing between 2008 and 2012, it can be concluded with some confidence that a recession of the US economy, which will be also part of a world economic crisis like the Great Recession, will occur again in the next few years.

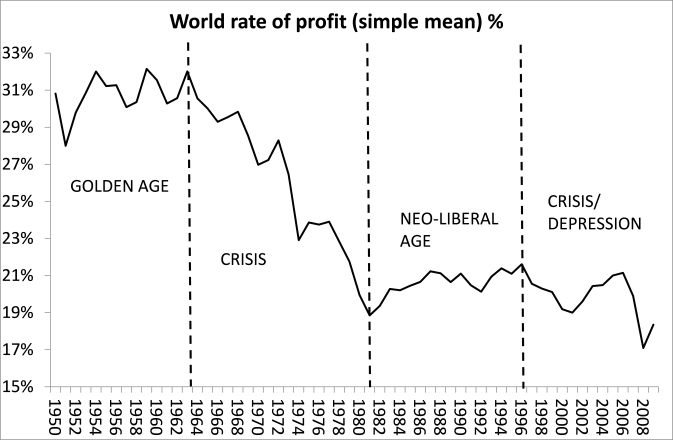

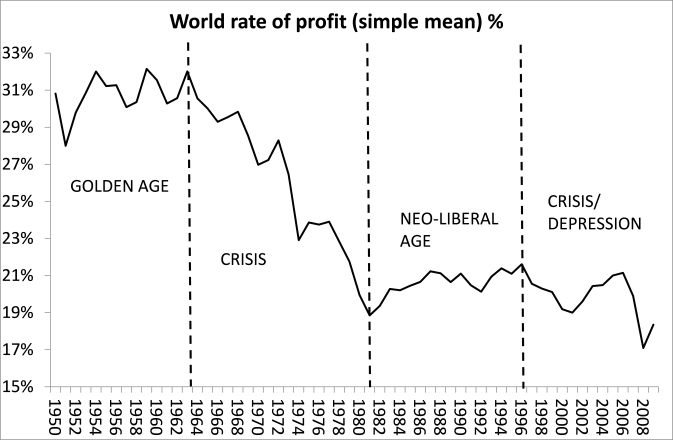

And Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall makes an even more fundamental prediction: that the capitalist mode of production will not be eternal, that it is transitory in the history of human social organisation. The law of the tendency predicts that, over time, there will be a fall in the rate of profit globally, delivering more crises of a devastating character. Work has been done by modern Marxist analysis that confirms that the world rate of profit has fallen over the last 150 years. See the graph below (data from Esteban Maito and ‘doctored’ by me).

Maito’s data for the 19th century have recently been questioned (DUMENIL-LEVY on MAITO), but in a recent work using different sources and countries, I find a similar trend for the post-1945 period globally (Revisiting a world rate of profit June 2015). And earlier groundbreaking work by Minqi Li and colleagues, as well as by Dave Zachariah, show a similar trend.

As Maito concludes: “The tendency of the rate of profit to fall and its empirical confirmation highlights the historically limited nature of capitalist production. If the rate of profit measures the vitality of the capitalist system, the logical conclusion is that it is getting closer to its endpoint. There are many ways that capital can attempt to overcome crises and regenerate constantly. Periodic crises are specific to the capitalist mode of production and allow, ultimately, a partial recovery of profitability. This is a characteristic aspect of capital and the cyclical nature of the capitalist economy. But the periodic nature of these crises has not stopped the downward trend of the rate of profit over the long term. So the arguments claiming that there is an inexhaustible capacity of capital to restore the rate of profit and its own vitality and which therefore considers the capitalist mode of production as a natural and a-historical phenomenon, are refuted by the empirical evidence.”

So the law predicts that, as the organic composition of capital rises globally, the rate of profit will fall despite counteracting factors and despite successive crises (which temporarily help to restore profitability). This shows that capital as a mode of production and social relations is transient. Capitalism has not always been here and it has ultimate limits, namely capital itself. It has a ‘use-by-date’. That is the essence of the law of profitability for Marx.

Alternative theories

This is not to deny other factors in capitalist crises. The role of credit is an important part of Marxist crisis theory and indeed, as the tendency of the rate of profit to fall engenders countertendencies, one of increasing importance is the expansion of credit and the switching of surplus value into investment in fictitious capital rather than productive capital to raise profitability temporarily, but with eventually disastrous consequences, as The Great Recession shows (The Great Recession; Debt matters).

Alternative theories of crisis like underconsumption, or the lack of effective demand, are taken from theories from the reactionary Thomas Malthus and the radical Sismondi in the early 19th century and then taken up by Keynes in the 1930s and by modern inequality theorists like Stiglitz andpost-Keynesian economists. But lack of demand and rising inequality cannot explain the regularity of crises or predict the next one. These theories do not have strong empirical backing either (Does inequality causes crises).

Professor Heinrich, after concluding that Marx did not have a theory of crisis and dropped the law of profitability, does offer a vague one of his own: namely capital accumulates and produces more means of production blindly. This gets out of line with consumption demand from workers. So a ‘gap’ develops that has to be filled by credit, but somehow this cannot hold up things indefinitely and production then collapses. Well, it is a sort of a theory, but pretty much the same as the underconsumption (overproduction) theory that Heinrich himself dismisses and Marx dismissed 150 years ago. It seems way less convincing or empirically supported that Marx’s own theory of crisis based on the law of profitability.

No other theory, whether from mainstream economics or from heterodox economics, can explain recurrent and regular crises and offer a clear objective foundation for the transience of the capitalist system.

Why not Marx’s law of profitability?

Finally, why do Professor Heinrich and others like Professors David Harvey,Dumenil and Levy and many other Marxist economists, want to dish Marx’s law of profitability as a theory of crises?

Obviously, they think it is wrong. But all these alternative theories have one thing in common. They suggest a way out of crises within the capitalist system. If it’s due to underconsumption, then spend more by government; if it’s due to rising inequality; then correct that with taxation; if it’s too much credit or instability in the financial sector, then regulate it. None of these leads to policies or actions to replace the capitalist mode of production at all but merely to correct or improve it. They lead to reformist strategies i.e. there no need to replace the capitalist mode of production with common ownership of the means of production and democratically controlled planning for need (socialism).

Then socialism becomes a moral issue to end poverty and inequality not an objective necessity if human society is to achieve freedom from toil. That’s a reformist view, but not Marx’s. Actually even these small changes that preserve capitalism might still require revolutionary action in the face of fierce opposition by capital – so why stop at reform?

Does Marx’s law fit the facts?

Some Marxist critics of Marx’s law of profitability reckon that the law cannot be empirically proven or refuted because official statistics cannot be used to show Marx’s law in operation. But there are plenty of studies by Marxist economists that show otherwise. The key tests of the validity of the law in modern capitalist economies would be to show whether 1) the rate of profit falls over time as the organic composition of capital rises; 2) the rate of profit rises when the organic composition falls or when the rate of surplus value rises faster than the organic composition of capital; 3) the rate of profit rises, if there is sharp fall in the organic composition of capital as in a slump. These would be the empirical tests and there is plenty of empirical evidence for the US and world economy to show that the answer is yes to all these questions.

For example, Basu and Manolakos applied econometric analysis to the US economy between 1948 and 2007 and found that there was a secular tendency for the rate of profit to fall with a measurable decline of about 0.3 percent a year “after controlling for counter-tendencies.” In my work on the US rate of profit, I also found an average decline of 0.4 percent a year through 2009. And here is a figure by G Carchedi for the rise in the organic composition of capital (OCC) in the industrial sector of the US since 1947 versus the average rate of profit (ARP). It tells the same story.

US ARP and OCC (i.e. C/V)

There is a clear inverse correlation between a rising organic composition of capital and a falling rate of profit.

Can Marx’s law explain crises?

How does Marx’s law of profitability work as an explanation and forecast of slumps in capitalist economies? The law leads to a clear causal connection to regular and recurrent crises (slumps). It runs from falling profitability to falling profits to falling investment to falling employment and incomes. A bottom is reached when there is sufficient destruction of capital values (the writing off technology, the bankruptcy of companies, a reduction in wage costs) to raise profits and then profitability. Then rising profitability leads to rising investment again. The cycle of boom recommences and the whole ‘crap’ starts again, to use Marx’s colourful phrase. There is a cycle of profit alongside the long-term tendency for the rate of profit to fall.

The evidence of this causality between profit and investment is available. Jose Tapia Granados, using regression analysis, finds that, over 251 quarters of US economic activity from 1947, profits started declining long before investment did and that pre-tax profits can explain 44% of all movement in investment, while there is no evidence that investment can explain any movement in profits. I find a higher ‘Granger causality’ of 60% from annual changes in profit and investment (unpublished) and a correlation of 0.67 for the period since 2000. And see this by G Carchedi (Carchedi Presentation).

In the period leading up to the Great Recession 2008-9, we can see the causality visually for US profits, investment and real GDP in the graphic below. The mass of US corporate profit peaks in mid-2006, investment and GDP follows two years later. Profits turn back up in late 2008 and investment follows one year later.

There are two basic regularities shown by the data: that a change in profits tends to be followed next year by a change in investment in the same direction; and that a change in investment is usually followed in a few years by changes in profits in the opposite direction. Thus we have a cycle. From these results, the “regularity” of the business cycle, and the fact that profitability stagnated in 2013 and declined in 2014 (and now the mass of profits in 2015) after growing between 2008 and 2012, it can be concluded with some confidence that a recession of the US economy, which will be also part of a world economic crisis like the Great Recession, will occur again in the next few years.

And Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall makes an even more fundamental prediction: that the capitalist mode of production will not be eternal, that it is transitory in the history of human social organisation. The law of the tendency predicts that, over time, there will be a fall in the rate of profit globally, delivering more crises of a devastating character. Work has been done by modern Marxist analysis that confirms that the world rate of profit has fallen over the last 150 years. See the graph below (data from Esteban Maito and ‘doctored’ by me).

Maito’s data for the 19th century have recently been questioned (DUMENIL-LEVY on MAITO), but in a recent work using different sources and countries, I find a similar trend for the post-1945 period globally (Revisiting a world rate of profit June 2015). And earlier groundbreaking work by Minqi Li and colleagues, as well as by Dave Zachariah, show a similar trend.

As Maito concludes: “The tendency of the rate of profit to fall and its empirical confirmation highlights the historically limited nature of capitalist production. If the rate of profit measures the vitality of the capitalist system, the logical conclusion is that it is getting closer to its endpoint. There are many ways that capital can attempt to overcome crises and regenerate constantly. Periodic crises are specific to the capitalist mode of production and allow, ultimately, a partial recovery of profitability. This is a characteristic aspect of capital and the cyclical nature of the capitalist economy. But the periodic nature of these crises has not stopped the downward trend of the rate of profit over the long term. So the arguments claiming that there is an inexhaustible capacity of capital to restore the rate of profit and its own vitality and which therefore considers the capitalist mode of production as a natural and a-historical phenomenon, are refuted by the empirical evidence.”

So the law predicts that, as the organic composition of capital rises globally, the rate of profit will fall despite counteracting factors and despite successive crises (which temporarily help to restore profitability). This shows that capital as a mode of production and social relations is transient. Capitalism has not always been here and it has ultimate limits, namely capital itself. It has a ‘use-by-date’. That is the essence of the law of profitability for Marx.

Alternative theories

This is not to deny other factors in capitalist crises. The role of credit is an important part of Marxist crisis theory and indeed, as the tendency of the rate of profit to fall engenders countertendencies, one of increasing importance is the expansion of credit and the switching of surplus value into investment in fictitious capital rather than productive capital to raise profitability temporarily, but with eventually disastrous consequences, as The Great Recession shows (The Great Recession; Debt matters).

Alternative theories of crisis like underconsumption, or the lack of effective demand, are taken from theories from the reactionary Thomas Malthus and the radical Sismondi in the early 19th century and then taken up by Keynes in the 1930s and by modern inequality theorists like Stiglitz andpost-Keynesian economists. But lack of demand and rising inequality cannot explain the regularity of crises or predict the next one. These theories do not have strong empirical backing either (Does inequality causes crises).

Professor Heinrich, after concluding that Marx did not have a theory of crisis and dropped the law of profitability, does offer a vague one of his own: namely capital accumulates and produces more means of production blindly. This gets out of line with consumption demand from workers. So a ‘gap’ develops that has to be filled by credit, but somehow this cannot hold up things indefinitely and production then collapses. Well, it is a sort of a theory, but pretty much the same as the underconsumption (overproduction) theory that Heinrich himself dismisses and Marx dismissed 150 years ago. It seems way less convincing or empirically supported that Marx’s own theory of crisis based on the law of profitability.

No other theory, whether from mainstream economics or from heterodox economics, can explain recurrent and regular crises and offer a clear objective foundation for the transience of the capitalist system.

Why not Marx’s law of profitability?

Finally, why do Professor Heinrich and others like Professors David Harvey,Dumenil and Levy and many other Marxist economists, want to dish Marx’s law of profitability as a theory of crises?

Obviously, they think it is wrong. But all these alternative theories have one thing in common. They suggest a way out of crises within the capitalist system. If it’s due to underconsumption, then spend more by government; if it’s due to rising inequality; then correct that with taxation; if it’s too much credit or instability in the financial sector, then regulate it. None of these leads to policies or actions to replace the capitalist mode of production at all but merely to correct or improve it. They lead to reformist strategies i.e. there no need to replace the capitalist mode of production with common ownership of the means of production and democratically controlled planning for need (socialism).

Then socialism becomes a moral issue to end poverty and inequality not an objective necessity if human society is to achieve freedom from toil. That’s a reformist view, but not Marx’s. Actually even these small changes that preserve capitalism might still require revolutionary action in the face of fierce opposition by capital – so why stop at reform?

The Marxist theory of economic crises in capitalism – part one

Last May, at the Marx ist Muss conference in Berlin, I debated with Professor Michael Heinrich on whether Marx had a coherent theory of crises under capitalism that could be tested empirically. Heinrich’s view, best expressed in an article he had written for Monthly Review Press in 2014, was that Marx did not have a coherent theory of crisis and, anyway, it cannot be tested as we only have official capitalist statistics. For something to read during this ‘Xmas week’, here is a revised version of my speech in that debate. The first part deals with the question of whether Marx had a coherent theory of crises or not.

Why do we care about the theory of crises?

Those active in the struggles of labour against capital internationally may wonder why some like me spend so much time turning over the ideas of Marx and others on why capitalism has regular and recurrent slumps and financial crashes. We know they do, so let’s just get on with ending capitalism through struggle and put aside the minutae of theory.

Well, there is good reason to understand the theory, because good theory leads to better practice. Yes, we know that capitalism has regular and often deep economic crises. These cause huge damage to people’s livelihoods and stop human social organisation moving towards a world of abundance and out of scarcity and toil. And crises are indications of the contradictory and wasteful nature of the capitalist mode of production.

Before capitalism, crises were products of scarcity, famine and natural disasters. Now they are products of a profit-making money economy; they are man-made and yet appear to be out of the control of man; a fetishism. Above all, crises show that capitalism is a failing system despite the great strides in the productivity of labour that this mode of production has generated in the last 200 years or so. It will have to be replaced if humankind is to progress or even survive as a species. So it matters.

Did Marx have a coherent theory of crisis?

What is it? It is a matter of intense debate among Marxists. There are various interpretations. Crises of capitalist production are due ‘underconsumption’, a lack of spending by workers who do not have enough to spend; or due to ‘disproportion’, the anarchy of capitalist production means that production in various sectors can get out of line with others and production can just outstrip demand; or it’s the lack of profitability in an economic system that depends on profit being made for private owners in order for investment and production to take place. In my view, the latter argument is the one that is both the best interpretation of Marx’s theory and also the one that is logical and fits the facts.

Some argue that Marx did not have a coherent theory of economic crises, and that was especially the case with Marx’s law of profitability. The argument goes that a reading of Marx’s works: Capital, Theories of Surplus Value and the Grundrisse, shows that Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is inconsistent and illogical.

For example, the law argues that the value of means of production (machinery, offices and other equipment) will, over time, rise relative to the value of labour power (the cost of employing a labour force) – a rising organic composition of capital, Marx called it. As value (and profit) is only created by the power of labour, then the value produced by labour power will, over time, decline relative to the cost of investing in means of production and labour power. The rate of profit will tend to fall.

But some Marxist critics say that this assumes that rate of surplus value (profit relative to the cost of employing labour power) will be static or rise less than the organic composition of capital. And there is no logical reason to assume this – indeed, the very rise in the organic composition will involve a rise in the rate of surplus value (to raise productivity), so the law is really indeterminate. We don’t know whether it will lead to a fall or a rise in the rate of profit.

But this is to misunderstand the law and how Marx posed it. The law ‘as such’ is that a rising organic composition of capital will rise and, assuming the rate of surplus value is static, the rate of profit will fall. But this is only a ‘tendency’ because there are ‘ countertendencies’, including a rising rate of surplus value, the cheapening of the value of means of production, wages being forced below the value of the labour power, foreign trade and fictitious profits from financial speculation. But these are ‘countertendencies’, not part of the ‘law as such’ precisely because they will not overcome the law (the tendency) over time.

As Marx said: “They do not abolish the general law. But they cause that law to act rather as a tendency, as a law whose absolute action is checked, retarded and weakened by counteracting circumstances.… the latter do not do away with the law but impair its effect. The law acts a tendency. And it is only under certain circumstances and only after long periods that its effects become strikingly pronounced.”

Marx argues that the law is based on two realistic assumptions: 1) the law of value operates, namely that value (and surplus-value) is only created by living labour and 2) capitalist accumulation leads to a rising organic composition of capital. These assumptions (or ‘priors’ in modern statistical language) are not only realistic: they are self-evident.

First, the law of value. The production of what Marx called ‘use values’ (things and services we need) is necessary to create value. But even a child can see that nothing is produced unless living labour acts. “Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish.”, Marx to Kugelmann July 11, 1868.

The rising organic composition of capital is also self-evident. From hand tools to factories, machinery, space stations, there is a huge increase in labour productivity under capitalism as a result of mechanisation. Yes that creates new jobs for living labour but it is essentially a labour-shedding process. While each unit of a new means of production might contain less value (due to the lower price of production of that technology) than a unit of an older means of production, usually the old is replaced by new and different means of production, or by a new system of means of production that contains more total value than the value of the means of production they have replaced.

As Marx explains in the Grundrisse: “What becomes cheaper is the individual machine and its component parts, but a system of machinery also develops; the tool is not simply replaced by a single machine but by a whole system… Despite the cheapening of individual elements, the price of the whole aggregate increases enormously”. As Marx put it: ‘It would be possible to write quite a history of the inventions made since 1830, for the sole purpose of supplying capital with weapons against the revolts of the working class.’ (Marx, 1967a, p. 436).

Higher productivity is not the aim of capitalist investment; it is higher profit. And to achieve that, capital needs higher productivity and labour-shedding new means of production. Was Marx right that capitalist investment leads to a higher organic composition of capital over time? He sure was. Look at this graph.

It shows a steady rise in the value of means of production (machinery etc) relative to the value of labour (measured in labour time) in the US since 1947. It also shows rising productivity (the labour time taken to produce one unit of things or services – LT). This is for the UK since 1855, as measured by Esteban Maito). So we have a rising organic composition of capital (VKxH) and a rising productivity of labour (falling LT) and a decline in the rate of profit over time (ROP). This is Marx’s law as such.

There are counter-tendencies but they do not overcome the tendency, the law as such, indefinitely. Why? Well, first, there is a limit to the rate of surplus value (24 hours) and there is no limit to the expansion of the organic composition of capital. Second, there is a ‘social limit’ to a rise in the rate of surplus value, namely labour (workers’ struggles) and society (social legislation and custom) set a minimum ‘social’ living standard and hours of work etc. This is the essence of class struggle under capitalism.

Did Marx drop his law of profitability as a theory of crises?

In a letter to Engels as late as 1868, over ten years after he first developed the law, Marx said that the law “was one of the greatest triumphs over the asses bridge of all previous economics”.?

But many Marxist critics reckon that Marx dropped this law as relevant as he did not seem to refer to the law after he expounded it in the late 1860s and looked more at the role of credit in crises (as Keynes and modern heterodox economists now do). Moreover, Engels, in editing Marx’s manuscripts after his death into Volumes 2 and 3 of Capital, made far too much of Marx’s law; indeed distorting Marx’s views on this.

Back in 1978, Jerrold Seigel had a look at the manuscripts. Yes, Engels made significant editorial changes to Marx’s writing on the law as in capital Volume 3. He divided it into three chapters 13-15; 13 was ‘the law’; 14 was ‘counteracting influences’ and 15 described the ‘internal contradictions’ (the combination of the tendency and countertendencies). Engels shifted some of the text into Chapter 13 on the ‘law as such’ when in Marx’s manuscript they came after the counteracting factors in Chapter 14. But in doing so, Engels does not overemphasise the importance of the law – on the contrary, Engels actually makes it appear that Marx balances the countertendencies in equal measure with the law as such, when the original order of the text reemphasises the law after talking about counter-influences. So, as Seigel puts it: “Engels made Marx’s confidence in the actual operation of the profit law seem weaker than Marx’s manuscript indicates it to be.” (Seigel, Marx’s Fate: The Shape of a Life, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1978, p339 and note 26).

Fred Moseley and Regina Roth recently introduced a new translation into English of Marx’s four drafts for Volume 3 by Ben Fowkes, where Marx’s law of profitability is developed and shows how Engels edited those drafts for Capital (Moseley intro on Marx’s writings). Moseley concludes that the much maligned Engels did a solid job of interpreting Marx’s drafts and there was no real distortion. “One can, therefore, surmise that Engels’ interventions were made on the basis that he wished to make Marx’s statements appear sharper and thus more useful for contemporary political and societal debate, for instance, in the third chapter, on the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.”

From 1870, Engels had moved from Manchester to London. So Marx and he met together as a matter of routine, usually daily. Discussions could go on into the small hours. Marx’s house lay little more than 10 minutes walk away … and there was always the Mother Redcap or the Grafton Arms. As late as 1875, Marx was playing with calculations of the rate of surplus value and the rate of profit. If Marx had really dropped the law as his most important contribution to understanding the contradictions of capitalism, would he not have mentioned it to Engels?

In the second part of this blog post, I shall look at the empirical support for Marx’s law of profitability as a theory of crises under capitalism.

Why do we care about the theory of crises?

Those active in the struggles of labour against capital internationally may wonder why some like me spend so much time turning over the ideas of Marx and others on why capitalism has regular and recurrent slumps and financial crashes. We know they do, so let’s just get on with ending capitalism through struggle and put aside the minutae of theory.

Well, there is good reason to understand the theory, because good theory leads to better practice. Yes, we know that capitalism has regular and often deep economic crises. These cause huge damage to people’s livelihoods and stop human social organisation moving towards a world of abundance and out of scarcity and toil. And crises are indications of the contradictory and wasteful nature of the capitalist mode of production.

Before capitalism, crises were products of scarcity, famine and natural disasters. Now they are products of a profit-making money economy; they are man-made and yet appear to be out of the control of man; a fetishism. Above all, crises show that capitalism is a failing system despite the great strides in the productivity of labour that this mode of production has generated in the last 200 years or so. It will have to be replaced if humankind is to progress or even survive as a species. So it matters.

Did Marx have a coherent theory of crisis?

What is it? It is a matter of intense debate among Marxists. There are various interpretations. Crises of capitalist production are due ‘underconsumption’, a lack of spending by workers who do not have enough to spend; or due to ‘disproportion’, the anarchy of capitalist production means that production in various sectors can get out of line with others and production can just outstrip demand; or it’s the lack of profitability in an economic system that depends on profit being made for private owners in order for investment and production to take place. In my view, the latter argument is the one that is both the best interpretation of Marx’s theory and also the one that is logical and fits the facts.

Some argue that Marx did not have a coherent theory of economic crises, and that was especially the case with Marx’s law of profitability. The argument goes that a reading of Marx’s works: Capital, Theories of Surplus Value and the Grundrisse, shows that Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is inconsistent and illogical.

For example, the law argues that the value of means of production (machinery, offices and other equipment) will, over time, rise relative to the value of labour power (the cost of employing a labour force) – a rising organic composition of capital, Marx called it. As value (and profit) is only created by the power of labour, then the value produced by labour power will, over time, decline relative to the cost of investing in means of production and labour power. The rate of profit will tend to fall.

But some Marxist critics say that this assumes that rate of surplus value (profit relative to the cost of employing labour power) will be static or rise less than the organic composition of capital. And there is no logical reason to assume this – indeed, the very rise in the organic composition will involve a rise in the rate of surplus value (to raise productivity), so the law is really indeterminate. We don’t know whether it will lead to a fall or a rise in the rate of profit.

But this is to misunderstand the law and how Marx posed it. The law ‘as such’ is that a rising organic composition of capital will rise and, assuming the rate of surplus value is static, the rate of profit will fall. But this is only a ‘tendency’ because there are ‘ countertendencies’, including a rising rate of surplus value, the cheapening of the value of means of production, wages being forced below the value of the labour power, foreign trade and fictitious profits from financial speculation. But these are ‘countertendencies’, not part of the ‘law as such’ precisely because they will not overcome the law (the tendency) over time.

As Marx said: “They do not abolish the general law. But they cause that law to act rather as a tendency, as a law whose absolute action is checked, retarded and weakened by counteracting circumstances.… the latter do not do away with the law but impair its effect. The law acts a tendency. And it is only under certain circumstances and only after long periods that its effects become strikingly pronounced.”

Marx argues that the law is based on two realistic assumptions: 1) the law of value operates, namely that value (and surplus-value) is only created by living labour and 2) capitalist accumulation leads to a rising organic composition of capital. These assumptions (or ‘priors’ in modern statistical language) are not only realistic: they are self-evident.

First, the law of value. The production of what Marx called ‘use values’ (things and services we need) is necessary to create value. But even a child can see that nothing is produced unless living labour acts. “Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish.”, Marx to Kugelmann July 11, 1868.

The rising organic composition of capital is also self-evident. From hand tools to factories, machinery, space stations, there is a huge increase in labour productivity under capitalism as a result of mechanisation. Yes that creates new jobs for living labour but it is essentially a labour-shedding process. While each unit of a new means of production might contain less value (due to the lower price of production of that technology) than a unit of an older means of production, usually the old is replaced by new and different means of production, or by a new system of means of production that contains more total value than the value of the means of production they have replaced.

As Marx explains in the Grundrisse: “What becomes cheaper is the individual machine and its component parts, but a system of machinery also develops; the tool is not simply replaced by a single machine but by a whole system… Despite the cheapening of individual elements, the price of the whole aggregate increases enormously”. As Marx put it: ‘It would be possible to write quite a history of the inventions made since 1830, for the sole purpose of supplying capital with weapons against the revolts of the working class.’ (Marx, 1967a, p. 436).

Higher productivity is not the aim of capitalist investment; it is higher profit. And to achieve that, capital needs higher productivity and labour-shedding new means of production. Was Marx right that capitalist investment leads to a higher organic composition of capital over time? He sure was. Look at this graph.

It shows a steady rise in the value of means of production (machinery etc) relative to the value of labour (measured in labour time) in the US since 1947. It also shows rising productivity (the labour time taken to produce one unit of things or services – LT). This is for the UK since 1855, as measured by Esteban Maito). So we have a rising organic composition of capital (VKxH) and a rising productivity of labour (falling LT) and a decline in the rate of profit over time (ROP). This is Marx’s law as such.

There are counter-tendencies but they do not overcome the tendency, the law as such, indefinitely. Why? Well, first, there is a limit to the rate of surplus value (24 hours) and there is no limit to the expansion of the organic composition of capital. Second, there is a ‘social limit’ to a rise in the rate of surplus value, namely labour (workers’ struggles) and society (social legislation and custom) set a minimum ‘social’ living standard and hours of work etc. This is the essence of class struggle under capitalism.

Did Marx drop his law of profitability as a theory of crises?

In a letter to Engels as late as 1868, over ten years after he first developed the law, Marx said that the law “was one of the greatest triumphs over the asses bridge of all previous economics”.?

But many Marxist critics reckon that Marx dropped this law as relevant as he did not seem to refer to the law after he expounded it in the late 1860s and looked more at the role of credit in crises (as Keynes and modern heterodox economists now do). Moreover, Engels, in editing Marx’s manuscripts after his death into Volumes 2 and 3 of Capital, made far too much of Marx’s law; indeed distorting Marx’s views on this.

Back in 1978, Jerrold Seigel had a look at the manuscripts. Yes, Engels made significant editorial changes to Marx’s writing on the law as in capital Volume 3. He divided it into three chapters 13-15; 13 was ‘the law’; 14 was ‘counteracting influences’ and 15 described the ‘internal contradictions’ (the combination of the tendency and countertendencies). Engels shifted some of the text into Chapter 13 on the ‘law as such’ when in Marx’s manuscript they came after the counteracting factors in Chapter 14. But in doing so, Engels does not overemphasise the importance of the law – on the contrary, Engels actually makes it appear that Marx balances the countertendencies in equal measure with the law as such, when the original order of the text reemphasises the law after talking about counter-influences. So, as Seigel puts it: “Engels made Marx’s confidence in the actual operation of the profit law seem weaker than Marx’s manuscript indicates it to be.” (Seigel, Marx’s Fate: The Shape of a Life, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1978, p339 and note 26).

Fred Moseley and Regina Roth recently introduced a new translation into English of Marx’s four drafts for Volume 3 by Ben Fowkes, where Marx’s law of profitability is developed and shows how Engels edited those drafts for Capital (Moseley intro on Marx’s writings). Moseley concludes that the much maligned Engels did a solid job of interpreting Marx’s drafts and there was no real distortion. “One can, therefore, surmise that Engels’ interventions were made on the basis that he wished to make Marx’s statements appear sharper and thus more useful for contemporary political and societal debate, for instance, in the third chapter, on the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.”

From 1870, Engels had moved from Manchester to London. So Marx and he met together as a matter of routine, usually daily. Discussions could go on into the small hours. Marx’s house lay little more than 10 minutes walk away … and there was always the Mother Redcap or the Grafton Arms. As late as 1875, Marx was playing with calculations of the rate of surplus value and the rate of profit. If Marx had really dropped the law as his most important contribution to understanding the contradictions of capitalism, would he not have mentioned it to Engels?

In the second part of this blog post, I shall look at the empirical support for Marx’s law of profitability as a theory of crises under capitalism.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario